Design in Dialogue #85: Michele de Lucchi

So, Michele De Lucchi, thank you so very much for taking part in Design in Dialogue. As one of Italy's masters of design and architecture who has left a significant mark on both of those creative areas, it really is a great honor to speak to you today. Thank you. So I am going to start with a very simple question. Where have we reached you today? In Milan, obviously. Or not?

No. -No. -No. I am in my studio. It's in Angera. Angera is the town I live in.

It's on Lago Maggiore. I've lived here on Lago Maggiore for many years now. And... every day I travel to Milan. And for a number of years, for 30 years, I traveled to Milan every single day, either on the train or in my car. And here in Angera I have this studio.

I predominantly work alone here in this studio. And here I... I predominantly work on my more artistic projects, or on projects that I create alone, where my work as the "author" of the work is important, where my role is that of the primary... the primary creator. I think this is a nice way to start our conversation, because the work of an architect and designer is much different to the work of an artist.

The... Designers and architects always have to satisfy a customer. And they have to satisfy a... either a company that has hired you to make a product, or a client who has hired you to complete an architectural project. But, in any case, the real... the real...

the real audience you are trying to please is always the wider public, so people in general. But when you work as an artist, the work that you do is much more solitary in nature. You primarily have to please yourself. Above all, you have to live up to your own ability to express yourself.

You have to satisfy your desire to test out formulas that allow you to understand your... your deliberations, your reasoning, your sensitivity. And I believe that design and architecture are work that must be done on two fronts.

They're not just work you have to do with others, in a team, in collaboration with many people, you have to do them for yourself. They are work you do by joining together your own sensibility and your own desire to express something. That's a very beautiful introduction, as a matter of fact, because one of the things that is very apparent in your work, is how vast it is. As it is, today we won't be able to even start covering all your work because of its multiplicity and your productivity, which are very impressive. - It starts within the framework of Radical Design, of groups like Cavart, Global Tools, Memphis, and Alchimia.

And then all the works you've done on a vast scale, for customers, like the architectural works that you've done in Georgia, Japan, Germany, Italy, and many other places. And with those three... branches, perhaps, or those three identities that we seem to see today, with AMDL Circle, if you say it that way, and Produzione Privata and your art works, that multiplicity is one of the things I would like to explore a bit more deeply today.

Yes. That's wonderful. Okay. Today I'd also like to... Given that we can't discuss everything, I'd like to make sense of the foundation of your work, to ask about some perhaps less well-known aspects.

And I'd like to ask about aspects that will help us understand what has driven your work, past and present. I have some images, but we'll look at them a bit later. That's because I'd like to start with a biographical question.

It has to do with your early beginnings. Your decision to study architecture in Florence. I'd like to know what steered you towards architecture? And why Florence? Well, the answer is a very personal one because... That's because it is something that also has to do with my... It concerns the period when I was a child and the fact that I am a twin. I have a twin brother, an identical twin.

And for very many years, no one was able to tell us apart. That included my mother. My mother couldn't always tell us apart. And in the end she just called us "twins." So she just called both of us.

That's because it was easier for her to think of us as a single child, as a single person. And being joined in that way, at a certain point it created a very strong desire to separate ourselves from each other. We had a great desire to be independent. We had a great desire to establish our own individual identities. And that is the reason I grew a beard. I've had my beard since I was 18 years old, so since the time I decided to study architecture in Florence.

Florence wasn't my city because I lived in Padua. It would have been much easier and more convenient to study in Venice. It has a famous architecture school. But I went to Florence. And I did that to distinguish myself, to separate, from my twin brother. And for many years we tried to do different things.

My twin brother became a scientist, a chemist. And then he later went to live in the United States. I stayed and went on living in Italy. He then eventually came back to Italy, to teach at the Ca' Foscari University of Venice. I worked with Ettore Sottsass, I had my experiences. And later, at a certain point, when my father and mother had died, we started to become closer again and now we are much closer than we were.

He's a painter now. He's retired from university teaching and he paints. So in some way or another, he too is an artist. He's trying to express himself too. And...

So, even if we are very different, we do also have some similarities. -Yes, the art... -There's an important thing to say. The thing is that instead of that being a handicap, it has been a great advantage.

It allowed me to establish my own personality. And I learned how important personality is for us, for people, but also for objects, buildings, architecture, and for ideas. Ideas don't exist without personality. So I put a beard on my ideas as well.

Very nicely put. And, yes, obviously, you're right. Many of your projects have a distinct personality.

That's something else I'd like to discuss further. And so your studies in Florence, in the 1970s, coincided with the decline, and in some way the fall, of Radical Design, at least from its heyday. Yes. I was very fortunate. I've been fortunate many times in my life, but I was fortunate at that time too, because I arrived in Florence at a time when Florence had a vibrant architectural studies program. There was a lot going on. There was a lot of cultural and intellectual tension.

There were extraordinary individuals, like Adolfo Natalini, people like Andrea Branzi... and many others. And I came into contact with those people. And then I moved to Milan. In Milan I met the other leading figures of the radical architecture movement, like Ettore Sottsass, Alessandro Mendini...

So I came into radical architecture at a very late stage, pretty much as radical architecture was ending. But I heard a lot, I was very involved in the ideas and the concepts of radical architecture. I'm convinced radical architecture provided the basis for the subsequent success of Italian design in the world, the success via the Memphis group, and the success of everything that made Italian design what it is. It isn't so much a commercial formula as it is a fundamental way of thinking, a way of interpreting the world of today, of interpreting industry and interpreting craftsmanship, and of interpreting people's need to portray themselves. Yes, the design culture is very intellectual, very cultural.

There's not... To put it a way that is much easier to understand. The concept of radical architecture was that architects shouldn't... They shouldn't... The architect's role isn't to devise houses.

An architect's role is to devise the... The architect fashions the behavior of the people who live in houses. The issue isn't that architects have to be creative. The issue is that architects need to make others creative.

You're not creative if you say, "Now I'll think and I'll be creative." That's not creativity. Creativity is when I say something or other, that stimulates other people's creativity and that makes other people creative. That's the architect's role. The role of the architect is to plan environments and objects that stimulate other people's creativity, and that make architecture and design protagonists in people's everyday lives, by how they affect the behavior of those who use those environments and objects.

So... the issue of the behavior, of the role of the architect, is very interesting. Now we can start with some of the images, or projects, that I'd like to talk about.

And the first one really does have to do with the issue of the architect's role. This image is, I believe, from when you were still a student, in 1973. The "Designer in Generale" performance at the 1973 Milan Triennale.

And, as you may have just explained, this is a protest against the concept that the designer is someone who dictates his will. Exactly right. The meaning of that performance was really to... It was to make an ironic declaration stating that a designer isn't a general, who imposes his idea, who imposes his... his taste...

his way of expressing himself and working. Instead, a designer is certainly someone who uses his own sensibility to interpret the sensibilities of others, to bear witness to the historical moment that he works and lives in. But do you believe that the... the battle that this general is engaged in, is a battle that one... Do you think it should go on today? Do you think that even today there is a false idea about designers and architects? Or has that changed since that time? I believe that the message, the message of radical architecture, is still very valid today. It's very valid today. It's still very right today.

It is also very apparent today, because design is really advancing through the provocations coming from designers as well. Those provocations become constructive when they are understood by everyone and used by everyone, and when they become something that has a wider impact, a broader impact, in society and on society's behavior. Maybe there's... I strongly believe in the ethical role of architects and designers.

In fact in Great Britain, where I am, and in many parts of the world, there is this idea of them having an ethical role and an idea of the architect as an almost "democratic" figure, more so than in the past, perhaps. Yes. Now let's turn to another project from that same period. It was a group that you were one of the founding members of. I'm talking about Cavart.

And I believe Cavart... You know this project very well too. I think very highly of the group. Maybe it's a little... Maybe it's less well-known compared to the other groups of that era. And the photos, the images are truly "arresting," as I'd say in English.

And Cavart was started while you were still a student, in 1973, with five other students. We talked about Radical Design and the strategy of forming a group. It is part of how the Radical Design movement operated. And it seemed that Cavart was somewhat a continuation of that strategy of working together.

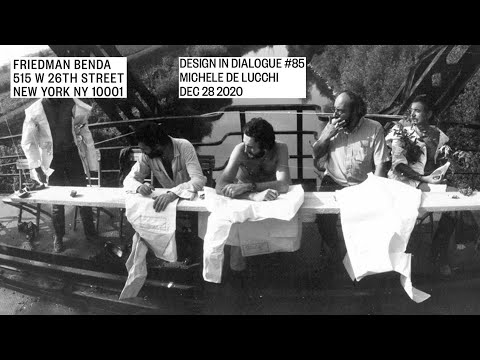

And so I'm interested in understanding what it was that drove you to create Cavart. And what were the ambitions, the ideas of the group? Yes. The photo we're seeing here is a very beautiful photo.

I'm there in the middle, shirtless. And then there's Gaetano Pesce right beside me. Then there's Ettore Sottsass next to me as well.

And they really were the people I admired the most at that time. And I still admire them today, because I certainly grew from that and was very influenced by their work, and by the part of my life that I shared with them. And the...

For us, the issue was really what I mentioned. We wanted to demonstrate that the architect doesn't necessarily have to devise... to devise houses or to produce objects, as much as architects really need... to stimulate creativity through their own work.

And stimulating creativity means coming into contact with the world, with the world around you. We really believed in the evolution of the world. We believed in the fact that every age was... was defined by... by an approach that...

by a defined mental set, and by a way of looking towards the future, and imagining a better future. So Cavart was really... It was... By the way, Cavart means the art of the quarries.

The art of the cave. In English it would be "art from quarries." That's because at that time, in 1973, the first protests of an environmental nature came to be. And near Venice, where the Euganean Hills are, there were trachyte quarries.

Trachyte is the stone used to build Venice. And those quarries had really... damaged much of the landscape and the environment of the Euganean Hills.

And that's how the name of the group arose. It meant "the art of quarries." Because we wanted to go and do... We wanted to do exhibitions, we wanted to do workshops and seminars within quarries.

And quarries had become... That's just what I mean. They had kind of become our everyday environment. We did a lot of events in quarries. They were places that were very... They were very pretty, very monumental. Almost like cathedrals.

But they were also challenging. It was as hot as hell in there. You can't imagine how hot it was, because there was no air moving. That's right. No shade either. And we invited architects to come there, and we invited friends, to design objects that we realized in the quarries. That was really to put the human environment in contact with human ambitions. Our hopes regarding the future, combined with our capacity to imagine the future.

That's how it was then and still is today, because even today the big topic is imagining the future. And imagining... a future, while always activating all of the capacities we have to think better and to think in a more productive and constructive manner. Indeed, that... That environmental vein that you mentioned, presents a...

I'm interested in how everything Cavart did took place, not just in the country, but far away from cities, far away from the centers of design. It seems to me that is also part of the protest against design. But that environmental vein... These images are related to that work. You really see it in your work from that time period.

It is much more... It was a bit ahead of the awareness that we have regarding sustainability nowadays. And so... Maybe you've already kind of answered this, but that ecological idea, was that something that continued with you from that period until today? Maybe in different ways in your work? Yes. Definitely.

That... The consciousness for survival on this planet has clearly always been very important. We can't design for this planet if we don't concern ourselves with what will become of this planet via the things we make. But not simply through what we create, but, above all, through what we imagine for the future.

Today, what we imagine is more important than what we actually succeed in doing physically. And at that time, back then, in 1973, 1974, environmental awareness was still a strange term. I have to say that my father and mother might not have even known what environmental awareness was. Because maybe it seemed like a fashion. It seemed like... Yes, it seemed like a concern that became interesting because everyone was drawn to the issue.

But it's not a fashion at all, it's a real paradigm shift that's a part of how we deal with everything we do today. And... And I certainly very much believe in all of that. And I believe it is very important to deal with the issue of the environment and sustainability, to be responsible for our planet, starting with what we do and with what we propose, including in the realm of imagination. I have a very important story to tell.

The story concerns a study that has shown that the countries that have a higher number of science fiction writers, are the countries with more technological development. That tells us that the imagination is deeply tied to reality. Imagination isn't something that is in people's heads, and the future is somewhere else. Imagination is strongly connected to... It is strongly connected to knowledge of the world and to science.

It's enough to consider the evolution of modern science, for example quantum physics, or subnuclear physics, and physical cosmology. Those are all things we can't comprehend with our senses. We can't see them with our eyes, feel them with our mouths, or touch them with our hands. More advanced science and more advanced knowledge is entirely built upon our capacity to imagine possible worlds, that are more complete, more intact, more capable of... worlds better equipped to respond to everything we know up to now.

To me that seems like a message pertaining to how important the arts are for our entire culture. What I mean by that is art's role in scientific development. I'm saying that because in England, in recent years, there has been too much of a division in education between science and the arts. It is also a bit as if the arts are not appreciated. But it plays all of these important roles, as you said. Art, that is.

Yes, but not just in England. That is sort of happening all over the world. There is a great tendency to move towards specialization. That is, to reduce problems down to the smallest possible, most understandable formula.

Because that's how you manage to best discover possible solutions. However, small... solutions become... Even if they're stirring, extraordinary solutions, they become small if you don't get the context in which these scientific discoveries and these technical solutions have been achieved. So there's always a need to see the world on a larger scope and in more... global terms.

That's something people have always complained about throughout all of history, from the Age of Enlightenment to today, people have lamented that paradox. To tackle questions properly you have to reduce them, and to see them better you have to broaden them. And that is a...

an issue you can't resolve by saying, "We have to specialize and only specialize," or, "We have to solely take a universal approach to things and see things on a large scale." We have to jump from one position to the other and see how the small things become big, and the big things become small. Indeed. This is a good moment to... to... to look at these images. One talks about the great...

the great contrast, from the avant-garde movement to the shift towards "scientific research" in your work. And I did in fact include these images to... to reflect on the end of the 1970s.

By that time Cavart was finished, and so was Radical Design, as we've already discussed. You had moved to Milan to work with the group Centrokappa. That was also the beginning of your relationship with Ettore Sottsass, with whom you collaborated at Olivetti from 1979, and later in the groups Alchimia and Memphis.

And I'm curious to... I've touched upon your work together, your relationship, a little bit, but I'd like to know more about how you met him, and your relationship. Considering the fact that he was 30 years older than you, he came from a much different background architecturally and culturally, than you did.

Yes, certainly. I met Ettore Sottsass during the radical architecture phase. And then later, in 1979, Ettore made me... He made me an assistant of his.

At Olivetti. Olivetti was an Italian company that made electronics and office furniture. It was a company that supplied office machines such as... It produced typewriters, and later computers, but it also supplied desks and office furnishings. And I have to say that the years there were very...

very interesting and useful. The time with Ettore Sottsass, with James Irvine, George Sowden, and many others. While there, we realized that designing an office wasn't designing desks and chairs, or machines, like typewriters and computers. Above all it was about considering how people experience their time at work and how people relate to... to work, to working with other people, to... to...

the... to the need to keep creating something that is new and more advanced. And to think about how they find the impetus in their social lives, and the ideas to achieve something better. When I see these photos today, they really look like prehistoric photos to me. That's because today it would be very, very wrong to live in environments like that. It would be senseless now.

But we have to remember that at that time, back in 1985, computers already existed, because Steve Jobs had already made his first computer in 1981. But... I have to say the... Yes, you can actually see a computer there, in one of those office installations. There was a computer and a typewriter. Yes, the...

The issue is technology has completely revolutionized how we work and our idea of what an office is as a workplace. The office is no longer a place that is devised to... to... to take people and put them all in rows, in order to make them productive together. Today the office is a place of creativity.

It's a place where people have to express their creativity. The office is no longer a place that is focused solely on production. It is the place where people meet each other, to... to receive from everyone who is present, the best messages they can pick up for a better tomorrow. That is a very... utopian way of thinking of that...

No. Oh, no, no, no! It's not utopian. No, the big multinational companies... The big multinational companies... I won't mention them all now,

but the American, British, Dutch, and German multinational companies, they know full well that to attract the best talented young workers, they can't bring them in to work in traditional offices. They can't bring in these new... these new people who are digital natives, to work at a desk in front of a computer.

They don't want that, because today's talented newcomers know that isn't the way to move towards the future. What they want most are stimulating environments, environments in which everything conveys a desire to think about moving forward and about the future. And that's what an office should create. That's what the office environment has to be able to provide.

That's also because we always work now. Today there is no longer a separation between working life and one's life at home, one's family life. A bit because families are much different now. But that's primarily because you can work anywhere. And work...

In the future, it will become ever more... It won't just be about... about producing something or other, it will really be participating in a wider world. That sounds like a very interesting consideration in a year in which... I haven't been in the office since...

in more than six months. And I actually don't expect to go back this year. -I really don't think so. -Yes, I know. Yes, but when you don't have an office that you can go to you notice the things that...

that the office gives us. You notice why we need that space. Yes, I'm convinced of that too.

Well, I actually included these images to sort of introduce your work from the 1980s, or the late 1970s, with those people, with Sottsass and with George Sowden, who you alluded to earlier. And... So let's go back in time a bit, because I'd like to talk a little about...

about a project or two from that period, that are between Radical Design and your more industrial work, such as the work you did at Olivetti. And so we have this work here, this very beautiful work. You did for Alchimia. This is the Sinerpica lamp.

I would simply like to ask you if you could give a little explanation of the idea behind this object. I can imagine that after quite a few years of not having designed objects, products, that this might have been one of your first functional objects. That is the first object I designed. It really is the very first one. And it is really... It is more a story than it is an object.

It's the story of a lamp that looks like a flower. And it grows like a flower grows. It's growing around a post. And it is... It is really an object that tells a story. This makes a lot of sense, even today, because all objects communicate.

And all objects have a story to tell. I think the desire that still exists today, to create new objects, to create new chairs, new lamps, new desks, even if there are already so many, originates in the fact that people have the desire to tell stories, and to listen. And telling stories and listening are the truly the job of the designer and the architect.

All the things that are made without any story behind them, are really the saddest of objects that don't have... They often don't have any reason to exist. And the fact that we're able to say that objects are stories is very... That is very important for defining the state of architecture and design today. They always tell stories, and not just fantasies.

They also tell us about innovations, about research, about experimentation. And... I am very pleased to have started with this... this practice of telling stories via objects, beginning with the very first object that I designed.

Yes, because this concept of design, of narrative design as you could also say, design with a personality, as you said earlier, that's something that wasn't all that widespread. It came a bit later. So it's very interesting to hear you talk about this object like that. Yes.

As a matter of fact, when looking at this object you recognize some other objects from that period. These objects have very strong personalities. It seems to me like these objects belong to a family of objects, a family that was born of a way of thinking. This is a very different approach to the one a few years later, by that I mean your work with Olivetti, but also the... One of your greatest design projects, the Tolomeo lamp, for Artemide. Obviously, you talked a lot about this object.

So... This very beautiful object. I would like to...

I put this picture up to demonstrate the great change in your work that I see during that period. It... It changed from a scale that was more made for galleries, with prototypes, models, things more for display, to being more for the world of industrial design, and also more for the world of architecture.

So you moved on to a grander scale. I'd like to know if that was an intentional change. Or perhaps it was just part of your evolution as an architect and designer. Yes. Well, as a matter of fact, to me all of these objects are born of a single concern. I want to find the most playful form, the most toy-like form, or the form that is more instrument-like, to really understand how a technology should look.

The issue of technology, of the appearance of technology, interested me very, very much. That was also because at the time I worked for Olivetti, which was an IT company, I was working for Memphis. The topic that I felt closest to was the question of how technology enters into contact with the people who use it and with the mentality of... of how to produce technological objects. I've always pursued the idea of making technology more simple, friendlier, more... more frugale.

I don't know if you can translate the word frugale into English. More familiar. So it doesn't cause angst. Some of the objects that we saw earlier were certainly very provocative objects, powerful objects, strange objects, ludicrous.

But provocation in design has always been advantageous for opening up new possibilities, and for opening up... for opening up alternatives to conventional things. We always have a need to put a strain on the things we already have, so we can generate enthusiasm for the things that are to come. And with the Memphis designs, I wanted to do just that. I need to say something. Memphis was, and still is, a company that works with craftsmanship.

The objects of the Memphis group are all products... are all handmade products. Handmade by machines, but they're produced one by one, or five by five, or ten by ten. They are products produced in small batches. The furniture done for Olivetti, the machines done for them, the computers, the printers, were produced industrially. And so in those years, I actually personally experienced the comparison between craftsmanship and industry.

They are not two separate worlds. They are worlds that are bound together. Because craftsmanship is the realm in which you experiment for industry. Industry needs craftsmanship. That's because it needs impetus. It needs to be... It needs...

to really be inspired. Inspired by new ideas, by new images, by new things. And craftsmanship functions as an experimental laboratory for industry. And that's what I did. I did that with Memphis before, and later with Produzione Privata.

I have always tried to experiment, with new objects, new techniques, new... new forms, new icons that could then become new icons for industry. So I have never experienced craftsmanship and industry as two separate worlds that do battle with each other. I've always seen them as a whole, as things from our modern world that are endeavoring to discover innovations, by experimenting on things that are handmade, and then implementing them in industry.

That is a very interesting observation. I am interested in the history of craftsmanship in Italy. But also because, as you said, you have long collaborated with craftspeople in Italy. But you have also worked with your own hands. You have made excursions into the world of craftsmanship with the Casette from 2004.

And that, moreover, is part of the great variety in your work, of which we see more and more. So I would like to know, in the context of all the other projects that we have spoken about, what attracted you to realizing these objects? And to doing it with your own hands, with a chainsaw. I have also heard that you have done performances while using a chainsaw.

Yes. I'm very good at using a chainsaw. I never use it on people, but I am good at working with wood. No, the real topic is experimentation. You experiment alone and with others. Everything is experimentation.

And when I made these objects, these little houses, these little architectural models, I really wanted to test the meaning of things made by hand, by implementing them on the grand scale of architecture. I wanted to really understand the meaning of the surfaces that you see in the wood cut by a chainsaw. What do they become when imagined on a grand architectural scale? And I also used these projects for professional projects, in which I later actually had to plan large buildings and make them realizable.

As we said at the beginning, working on a small scale or a large scale, specializing in small topics and then knowing how to carry them over in more expansive, more open environments, is always a useful and interesting formula for understanding better... for understanding what happens to things, and for... for... for avoiding doing things as they have always been done. That is a lovely explanation.

In fact, I have some images of... I found this because... It's very, very nice. I liked this photo of a performance of yours.

But we also spoke a bit about... We spoke about Produzione Privata and all the pretty objects. I can see that we don't have loads of time left together now. Given that, at this moment I'd like to return to the past again. Also... I'm there right now.

I'm sitting at that window. Ah! Okay. But I came by one day to Il Chioso, to the archives. And... -Really? -Yes, many years ago. To do research. And I was really struck when I visited there, because it seemed like you had kept every notebook, every sketch, from your time as a student on.

And that was fantastic for a historian. I remember being in the archives. It stayed with me, also because it is a very beautiful place. It is on the lake, as you said.

For a long time I've been curious to know what drives that impulse to preserve things, to archive your work. Do you return to earlier works for current projects? Yes, well... Well, I have to mention that in 2002, the Centre Pompidou asked to take on many pieces from my archives. There were lots of radical architecture pieces.

Things like the first models of Tolomeo and my objects from Produzione Privata went to Paris, to the Centre Pompidou. They're safely kept there. So when I realized that the archive could be useful, and not just for looking back but also for looking ahead, I then started, not so much to collect everything, but... to collect things that seemed best suited for combining with potential future experiments. The issue of the future has always been very, very important to me.

It's certainly more important than the past and the present. Seeing... It is to understand how what I'm doing now can then later be put to use by new generations, to deal better with what will come after me. The... And I have to say that the topic of...

of a specialized world and a global world, a more holistic world, a more complete world, that is a topic that interests me very much at the moment. I've seen many people address it nowadays, primarily philosophers and scientists. There are branches of philosophy and science, that are trying to understand how to bring together many experiences that are now being made independently of one another, but when put together they take on a new meaning that is much more complete, much richer.

And it's the same with architects and designers and artists. I think when they are joined together, they explain much better the meaning of scientific enquiries into what's happening today, that can then be projected into the future. That's also the reason I did the Circle. I created the Circle to be able to see, on a grander scale, what I, when I focus on what I'm doing, see solely in the minutest of details.

And the idea of a circle, of a circle itself with an environment that embraces a lot of things, does a very good job of explaining the meaning that we have to give research today, and the meaning that we have to give to work today, to working together. By combining many areas of expertise, we have the possibility to delve deeper nowadays, rather than to just probe into one area of expertise. As an individual, I imagine. Because... As an individual, yes. The meaning of the Circle is really a circle of people, a circle of various areas of expertise, a circle of various disciplines, a circle of various areas of knowledge. There are lots of circles that we have to be able to move as far as possible towards one position, towards one way of thinking, to discover on a wider scale how we are built and what we want.

I understand how that way of working makes a lot of sense. Having a circle with so many areas of expertise offers great opportunities when you combine them. But also...

I'd like to know this. When you look at the Circle, which includes lots of different works, when you look at it along with Produzione Privata and the works of art, those things, they seem to me to be... It's a lot for an individual to keep an eye on, to keep a handle on and to keep in your head. And I'd like to know if it presents a challenge as well as an opportunity for you.

Yes, well... my real work is to try to understand the meaning of objects. The meaning of objects understood as objects, like a computer, a pen, a pencil, notebooks... Every object, but architecture as well. Architecture also consists of objects. Environments consist of objects too. Objects create environments, environments don't create the objects.

And giving meaning to objects means giving the objects value. It's about understanding what has worth and what doesn't. It's about realizing what's missing and what there's too much of. It's really about understanding humankind in its most immediate manifestation, in its objects. The only things one can combine. There's such great diversity of forms, such a great diversity of stories, such a great diversity of customers and of project subject matter.

The fact is, everything I've done has always been objects. But they are objects that... that have a value because they tell a story, because they represent a moment, they open up our vision, they open up the imagination.

They have value because... because they present problems and address certain problems. That is the meaning that we can give contemporaneity today, and that we can give to everything, to the great multitude of impulses that we receive from the modern world. It is very interesting to think of architecture as an object like that.

On that note, I would like to ask you if you... Did you, therefore, also construe this project as... This is the last...

image of a project of yours that we can talk about today. As this is one of your most recent projects, I'd like to know how this fits in with everything that we've talked about today, including with your vision for design and architecture. That is a library. It's a library. It is a library of knowledge. Libraries are places...

Whether it's a digital library or a library with real books in it, it is a place of knowledge. And a place of knowledge is a place of cognitive experience. Cognitive experiences are always circular experiences. You're right that this takes us back to the Circle, because every one of our experiences consists of a stimulus, of a process of understanding, of questioning it, and of going back to discussing it again and reconsidering it. It's all a circle. This library is also circular. And it brings together two banks, two different positions.

Knowledge is necessary for bringing together what is always a dual relationship that we have with others, that we have with what we know and what we want to know. Today it's in the present and it will be in the future. It all has a dual... It all has two sides, two banks.

And it all has a way about it. It all has to be created to bring the two positions together. Democracy is always about combining different stances. We don't have a way out of that as human beings. If we want to grow, if we want to create a destiny that is brighter for this planet, one way or another we have to continue to join the two banks of rivers.

To me that seems like a perfect message to end our conversation on. And the metaphor of the circle to unite the hour that we've had together. There were so many things that we were unable to talk about today, but I really want to thank you because this was fascinating, not just for me, but for everyone who will be in the audience. I hope it was also interesting for you to have this talk.

Certainly. It has been a nice plunge into my life, a nice plunge into the questions I've asked myself. And a plunge into the answers I've given. And I realize, that I have lots of answers that I still have to find and still have to give.

That's a really lovely way to finish. -Okay, thank you so much. -Thank you. Okay, bye. Thank you. Hope you come to Milan. Oh, me too. Yes, do that.

2021-01-03 17:37