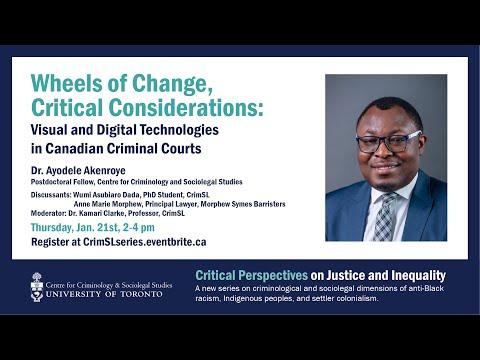

Wheels of Change, Critical Considerations: Visual & Digital Technologies in Canadian Criminal Courts

Okay let's try that again I’ve had to resolve that so sorry about that I’m Kamari Clarke, a professor at the Centre, and I’ll be moderating this session today. I would like to begin with a land acknowledgement in order to express gratitude to those who reside here, and to honour the Indigenous people who have lived and worked on this land historically and presently. “We wish to acknowledge this land on which the University of Toronto operates. For thousands of years it has been the traditional land of the Huron-Wendat, the Seneca, and most recently, the Mississaugas of the Credit River.

Today, this meeting place is still the home to many Indigenous people from across Turtle Island and we are grateful to have the opportunity to work on this land.” While we seek to understand our history and place here that has brought us to this land. This expression of gratitude is a way of honouring the Indigenous people who have been living and working on the land from time immemorial, and say thank you. Today, I have the pleasure of introducing the lecture and our guest and I will of course be moderating. The lecture takes on a range of key and critical developments since the onset of COVID-19 and the requirements for physical distancing.

And as a result, several Canadian courts embraced digital technologies to conduct remote hearings of cases. This has included the e Supreme Court of Canada. What we have seen is the way that digital technologies in criminal courts have led some to advocate for their expanded use after COVID-19. While on one hand, using digital technologies in our criminal courts has proven beneficial, on the other hand it also has had cultural and political implications for how we understand the role of the judge, the accused persons, as well as the accused person's perception of this role, it raises a whole set of questions about pervasive social inequality and one of the key questions that will be at the core of our discussion today and of the presentation really has to do with the extent to which video conferencing technology is actually changing the social landscape and the implications for social inequality in our world and we're interested in the implication for ratio, the ratio of people and people in general, and what this these technologies mean on this changing landscape. But before we go to what is going to be really a an exciting conversation both presentation and conversation with our moderators or commentators, let me just go over a couple of logistics related to the event for today, the event will be live streamed via YouTube it is being live streamed now as we speak.

The format for today is one where the presenter will introduce his paper he'll have about 50 minutes to do that, and then we will have two responders who will comment both affiliated one a graduate student a PhD student in our program and another a faculty Member who is teaching in the program and so they'll have about thirty minutes 15 each to comment on the paper and then from there we'll give professor Akenroye a chance to respond and and then we'll have an additional half an hour to 45 minutes for questions and comments. Questions and comments will be taken in the chat so feel free to put them in the chat as we're going along, of course, on the YouTube chat. So, as we go along or toward the end that's fine as well, and when we get to that point I’ll be keeping track of the questions reading out the questions and asking our speaker as well as our um discussants to engage in some of the questions in the chat And so, so that's the plan for today we have about two hours, so we all my job will be to moderate and to try to move up the long and it really is a pleasure to to engage in a topic that's so significant and has serious consequences, both in the ways that COVID-19 is being managed this pandemic is being managed in in our own backyards but also what the implications are for future adjudicatory processes in our country, and so the first so next I’ll introduce our guests it's really a pleasure to introduce Dr. Ayodele Akenroye who is currently a Postdoctoral Fellow at the Centre for Criminology and Sociolegal Studies at the University of Toronto. His ongoing research closely interrogates the use of videoconferencing technology in Canadian criminal courts and how its usage clashes with the Charter rights of accused persons. In this regard, he is interested in challenging the cultural assumptions

about how the role of the judge is performed and the image of what the judge ought to be. Dr. Akenroye is also a Tribunal Member he's an immigration judge with the Immigration Division of the Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada with the Government of Canada where he makes decisions in admissibility hearings and detention reviews for foreign nationals or permanent residents believed to be inadmissible to, or removable from Canada under the law, or detained by the Canada Border Services Agency. And so he really does come with a wealth of

experience, especially of late, and in the what he draws from his research and to date he's much of the work that he's presented it's a work in progress that is also being supplemented by qualitative and quantitative work. He received his Bachelor of Laws Degree from Obafemi Awolowo University in Nigeria in 2007; a Master of Laws Degree in International Law from the University of Manitoba, and then a PhD most recently International Criminal Law from McGill University in Montreal, and that was in 2018. now uh he's he has extensive of course law experience in multiple fields he has served uh acted as the deputy chief commissioner of the Residential Tenancies Commission with the Government of uh Manitoba and he has been called to the court to the bar in Ontario and has practiced as a criminal barrister before different courts in Canada he also has tremendous it's worth saying this because the paper is certainly concerned with um some of these juridical questions about law and the judge and law making and um so it's not just the domestic but in the international realm Dr Akenroye has years of experience working in international criminal law and it's actually in that context where I came to know him and and his work when he was working as a professional a legal professional for the International Criminal Court in in the Hague and also under the uh he has worked with ECHOWAS Commission in um in Abuja Nigeria so I could go on and on with his bio as a young and up and coming scholar he has tremendous work experience and has done tremendous work not only in Nigeria uh and in the African context but um in relation to international criminal law and so it really is a pleasure having him at the Centre he's the author of book chapters articles um and he really is a wonderful interlocutor so it's a pleasure to have him with us today his talk is entitled Wheels of Change, Critical Considerations: Visual and Digital Technologies in Canadian Criminal Courts so please join us in welcoming our guest today Dr Ayodele. Thank you, thank you. For the introduction I’ll be sharing my screen now, so please give me a minute to share my screen.

Can you see my screen. Yes, we can see it fine Good Thank you. Good afternoon and thank you for attending my talk today. I want to start by thanking Prof. Kamari Clarke for giving me the platform

to conduct my research at the Centre and for acting as the moderator this afternoon. I also want to appreciate Prof Audrey Macklin and all the good people at the Centre for Criminology and Socio-Legal Studies for giving me the resources to conduct my research on digital justice in Canadian Criminal Courts. Let me start by sharing a work story.

In my other capacity as a tribunal member, I have immensely enjoyed the ease of using technology to conduct hearings remotely, but it wasn’t until a person incarcerated in a provincial jail who was appearing before me via teleconference referred to me as “Bro” and consistently referred to me throughout the entire administrative proceeding as “Bruh”, “Bro” "bra" or its variations, that I had an awakening that while using technologies to conduct hearings is beneficial, it could undermine the fundamental tenets of our entire judicial system, grossly distort the image of a judge and be prejudicial to the interests of the persons appearing before our courts. My objective in my presentation today is to illuminate or to explore how the adoption of videoconferencing technologies such as Zoom, Webex, Ms Team and other electronic platforms in Canadian Criminal Courts are challenging the legitimacy and authority of the Judge and reshaping and renegotiating the cultural image of a judge. This presentation is part of my larger postdoctoral study at the University of Toronto and it is far from been concluded, so feedback and comments on my study are welcome. Since March 2020 when COVID-19 was declared a pandemic worldwide and the resulting imposition of related restrictions on travel and in-person gatherings, most courts in Canada cancelled all previously scheduled trials. This led to an exponential increase in the already sizeable backlog of cases waiting to be adjudicated, affecting the mental health of people in detention due to the increased use of medical isolation, quarantine and solitary confinements as measures to contain the spread of the virus in prisons, and eventually eroding victims’ confidence in the ability of the criminal justice system to deliver a fair verdict. Stakeholders such as criminal defense lawyers critiqued the Canadian criminal justice system as being outdated, archaic and heavily reliant on close physical contact, paper documents and personal appearance —all outdated approaches that have failed to adopt new technologies at the same pace as other Canadian institutions.

This led to a strong push for Canadian courts to adopt videoconferencing technology to deliver meaningful justice to the accused, victims, witnesses and people, such as First Nations constituencies, in remote locations. As a result, there is an increasing use of video-conferencing technological capabilities in the criminal justice system in case preparation, plea negotiations and potentially for trials. In fact, courts across Canada have increasing accepted videoconferencing technology as a fair and efficient way to move judicial proceedings forward in the face of the pandemic. Grounded in this new reality, the Ontario Government reallocated the funds earmarked to build a new courthouse in the Halton Region to technology, arguing that that it is high time to modernize the justice sector in Ontario and investing significantly in technology to take Ontario courts online is the way to go.

Canada is not alone in embracing videoconferencing and investing in technology. Courts around the world are investing in technology solutions and are replacing face-to-face hearings with audio or video hearings using technology platforms such as Zoom, Ms Teams and Skype. As courts in Canada undergo rapid transformations, the physical courtroom is becoming a contested space in which questions abound about the importance of the administration of justice reflecting the changing needs of society.

Through this narrative, there is an assumption that the integration of videoconferencing technology into the courtrooms would reduce cost and increase access to justice without putting accused persons at a disadvantage or breach their procedural rights. While this could be true to an extent, the alternate narrative is that videoconferencing technologies disrupt and call into question longstanding assumptions about the need for a physical location as the central domain for the authorial execution of justice. Through space, the hallowed halls of the court room, the declaration through speech, acts that all should rise for the judge to be seated - the actual physicality of hierarchy is disturbed. Both sets of narratives highlight the image of a judge but one demands contemporary solutions to contemporary problems and the other insists of the necessity of ritualized space to be central to the authorial power of the judge.

In reflecting on this dynamic, what we see at the heart of the contestations is the contemporary nature of judgecraft. Through the identification of judgecraft as a process for the skilful management of legal decisions through not only the use of various technological tools to interpret and apply the law but also the presumed command of the authority of the court through the perceived legitimacy of its office, I argue that it is the production of authority and power alongside the technocratic tools to rationalize legal decisions that are at the heart of contestations. In doing so, what we see is that there is a need to closely interrogate how the legitimacy of the judge is challenged and the social control wielded by judges is lost in the process. These questions are not merely academic or tangential but the stakes in the move to virtual hearings are high particularly in the criminal justice system where Canadian courts must zealously protect the Charter rights of accused persons, including the rights to speedy trial, confrontation of witnesses and an open courtroom. I will now turn my attention to the role of architecture in our court system. Since antiquity, authoritative justice has been performed at a “proclaimed place” known to the entire community.

While the “proclaimed place” is not fixed and has evolved over time from outside like the stones on which the judges sat as depicted on Achilles’ shield in the Iliad, or the trees under which the South African community tribunals were traditionally convened, to the present day modern imposing courtroom architecture primarily dedicated to the adjudication of disputes. Courthouses are designed to symbolize certain ideals and community values in the public sphere and define the sorts of acceptable behaviours and experiences that participants experience in inside. It also signals that the place of the trial is in some way special and out-of-the-everyday. This fosters the basic political legitimacy of courts everywhere and the social control it exercises over the participants in the justice systems as well as the general public. Over time, the physical place of justice has been synonymous with the location of the judge and physical courtrooms are widely believed to imbue judgecraft with “a mystique of authenticity and legitimacy”.

The contemporary carefully conceived and curated iconography of the physical courthouse conveys to the public and all the participants who attend its “hallowed hall of justice” of the society’s ideals of how justice is to be dispensed in the maintenance of law and order and the promotion of shared community values. According to Piyel Haldar, “architecture marks off and signifies that authority-to-judge which can only be found inside a court of law and nowhere else; it assigns legal discourse to a proper place.” For instance, in constructing the Supreme Court of Canada building in Ottawa, the goal was clearly communicated as ‘…for the highest court in a democracy, the architect had to convey an impression of unquestionable authority, through the use of vast proportions and a severe décor, and transparency of action, symbolized by natural light…’ By its very nature, attending a physical courthouse conjures an understanding of being part of a special and culturally acknowledged type of activity which requires appropriate behaviours. Nothing represents the society’s conception of justice being not only done but seen to be done than the spectacle of trial by jury – “peers” in our criminal courts. The carefully spatial layout of the courtroom with the royal coat of arms behind the raised dais where the judge sits representing the full majesty of the law, the docks where accused persons are seated while waiting for the verdicts of their peers, and the twelve juror – “wise men” - seated in their jury box, lawyers fully robed in their legal regalia, witnesses called and sworn to tell the truth, the whole truth and nothing but the truth and court proceedings watched by the public and reported by the press or court watchers all contribute to distinguish the office of the judge, promote the legitimacy and the authority of the judge who is charged with the role of making life-changing pronouncement on behalf of the community. Therefore, judges’ decisions require particular social, temporal and spatial framing to have effect and the need to establish a special judicial space – a civic space – through which these pronouncements are made, is therefore important to help legitimate the adjudication.

I will now turn my attention briefly to how the Supreme Court of Canada has interpreted this The first-ever fully virtual hearing of the Supreme Court of Canada has concluded – June 9, 2020 through Zoom and livestreamed on the court's website. In his opening speech, the Chief Justice of Canada – Right Honorable Richard Wagner said open court just remember that we are here for your arguments, not the angle of your camera or your facility with the mute button will get through this hearing, just as we get to this pandemic and of court. Excuse me. Ayo I’m sorry about this, you may not realize but we're having an issue with the the translation. And the there's a suggestion that perhaps we ask you to turn off your camera and that might allow us to see the the translator the sign translator. And if you could just turn it off, while we're watching the the the PowerPoint that might help so that others who need the the translation can actually see the sign interpreter. So if you don't mind if you don't mind turning off your camera will still hear you and we'll see your PowerPoint and then as soon as you're ready to release the PowerPoint you bring back on your put back on your camera is that OK, with you.

That works for me. So sorry for the interruption, no problem, no problem. Okay, so let's see if this works, then, if we're able to see the interpreter. Maybe I know if you could start speaking yet turn off the camera, and if you start speaking, we can see if the interpretation can happen, alongside your presentation thank.

is OK now to proceed. Why don't you start continue and we'll see if we can. Okay, working and I’ll let you know, thank you, sorry about that okay great so. The Chief Justice of Canada said on an open court again so that I can go back to that quote he said “..Just remember that we are here for your arguments, not the angle of your camera or your facility with the mute button.

We will get through this hearing, just as we will get through this pandemic." And of course, there was a hiccup – one of the counsel appearing had issues with his sound and video and the Supreme Court had to take a break to resolve the technical glitch. Let’s look at what happened just 3 months after this first virtual hearing. On September 22, 2020 – the Supreme Court of Canada conducted the first physically- distanced hearing.

In a notice to the public, the Supreme Court stated that measures were put in place in the courtroom to meet physical distancing requirements, and hearings will also take place by way of videoconference for counsel who cannot attend a hearing in Ottawa. Even in this hybrid format, you can see some court room rituals were practised. I will now turn my attention to the role and place of rituals in court.

Centrally located in the legitimation of the law-making role of the judge is the role of rituals in legitimizing their decisions and judgments. Rituals such as the stare decisis doctrine, doctrinal formulas, and rules of procedure were considered to be nothing but “magic solving words”, “word rituals”, or “legal myth” concealing the influence of personal preferences and ideology on decision-making. For instance, the all-familiar long-standing court rituals of the court clerk ushering in the judge by yelling “ Oyez, Oyez, Oyez, anyone having business before the Queen’s Justice of the Superior Court of Justice draw near and you shall be heard, Long live the Queen”, court participants standing up when the judge enters, and bowing to the court on departure, all have performative effects of casting the judge as an independent authority and the custodian of our community values. It also set the stage for the acceptable civil modes of address and well as respectful and polite behaviour expected of all the courtroom participants. Thurman Arnold refers to judicial rituals as “magic realism” which posits that symbolic aspects of judicial practices are useful and have practical relevance; and the character of judicial systems would thus be profoundly altered if we were to do without this folklore and spiritualism. Allen theorized judicial rituals as “a ritual-magic mode of adjudication that is not necessarily contrary to legal reason.”

The primary function of adjudication is not to explain the decision but to transform the social fabric: [L]aw constitutes and transforms social meaning by helping to create and recreate the social situations at issue in adjudication. Ritual magic is a long-recognized mechanism of such transformations. In law, as in ritual magic, transforming the meaning of a set of social circumstances can happen through common formal and performative techniques that may look like mere distractions or ways to disguise what is really going on. In fact, some functions of law in our society may depend on these techniques, not because they confer logical-rational correctness or predictability, but because they may contribute to judicial impartiality and because they may provide a mechanism through which official legal decisions take on some of the affective power of lived experience and so generate the personal and collective commitment that leads to social transformation. In particular, rituals reaffirm the power of judicial decisions by replicating and re- enacting conflicts in a symbolic fashion during trial, they enhance the judge and jury’s impartiality, and they symbolically replicate the triumph of social life over death and morbidity. In an essay on judicial rituals and the functions of judging, Antoine Garapon, a French magistrate and author, argues that judicial rituals are a condition sine qua non for law to exist in practice.

He identified three functions of judicial rituals at trial: (1) breaking out of ordinary experience, (2) purifying the experience of crimes that are re-enacted during trial, and (3) representing and commemorating legitimate authority. Rituals put tensions at ease and defuse violence by transforming real fights into symbolic struggles. He argues that the actual person of the judge does not count as much as his or her symbolic figure. The judge is a fictitious entity, just as the legislator is.

He or she carries out an act of speech, which gains, by virtue of the surrounding ritual, a performative function. In other words, with the ritual and robe, a judge renders justice whenever he or she utters the law. Garapon argues against the desacralization of judicial rituals. Without rituals, it becomes difficult to know who renders an authoritative decision. Without rituals, the decision of a judge is no longer presented as being the right decision. This could result in the reasons for the decision being questioned, and indeed, even in

the disappearance of a need to give reasons. One of the central arguments in the use of videoconferencing technology is that the criminal justice system needs to undergo structural reforms in order to make adjudication of trial more efficient and in achieving this objective, there is a need to reduce or completely discard judicial ritual which can be time- consuming and expensive. But the reality is that the entire judicial system is built around rituals in other to provide it with the self-sustaining logic and legitimacy and a de-ritualized criminal adjudication may result in the loss of legitimacy for the judges. It is therefore necessary to consider that there may be other ways of creating judicial rituals in order to produce legitimate decisions. For example, greater participation by the parties, including an opportunity to define the appropriate rituals, could not only ensure that judicial rituals remain at the forefront of any decision rendered, but also that the dispute resolution process is more efficient. I will now turn my attention to the Image of a Judge With the increasing adoption of videoconferencing technologies, particularly in the context of COVID-19, the unique image and role of the judge is being renegotiated, dispersed and their relationship with court participants and the public has dramatically shifted as judges are now not confined to the same courthouse or courtroom as other participants. Court proceedings are now

a spatially distributed event extending the boundary of the court to other buildings, such as libraries, lawyers’ offices, police stations and now the private homes of accused persons. The wholesale migration to remote hearings with the use of videoconferencing technologies such Zoom, Webex, Ms Teams, and other virtual platforms disrupts the way judges usually appear to court participants, how they are imagined culturally and the mystique and aura that judges have enjoyed historically is likely stripped away. Remote hearing tends to remove some of the perceptual cues which normally trigger the performance of long-standing symbolic and performative rituals as previously discussed and different empirical studies conducted in Australia, the UK and the US show that attending court from remote locations significantly alter the experience of justice for all involved.

The lack of formality and highly dispersed distributed court environment that remote hearings portray has significant implications on the experiences and outcomes for judges, accused persons, victims and indeed the Canadian public, this requires further interrogation, and I will attempt to do so. The public facing aspect of the role of a judge helps to create and sustain their cultural image. As previously discussed, the judge embodies the authority of the court, as the final arbiter of disputes with the integral role of managing the court and other courtroom participants. Rowden and Wallace argued in their work that any dissonance between the image of the judge and the nature of their role potentially detracts from their effectiveness because courts, unlike other branches of government, rely on public acceptance of their legitimacy. In a typical criminal court with an adversarial model, the judge is tasked with conducting preliminary hearings, taking guilty pleas, presiding over trials, sentencing accused persons, delivering rulings or judgments and hearing appeals with the integral responsibility of controlling and monitoring the proceedings to comply with the applicable rules of evidence and procedure and ensuring that all the courtroom participants behave appropriately. The judge decides what evidence is admissible

and how it is given, such as whether in the form of in-court testimony or by video link. The judge may also direct questions to a witness although this has to be carefully done. A judge with the fact-finding mission will listen to evidence presented throughout the trial and draw conclusions from them to make a determinative decision.

This might include forming opinions as to the credibility and reliability of a witness to determine if the witness is telling the truth or not. In a jury trial, the judge sums up the facts for the jury and direct them as to the applicable law in reaching their verdict. This fact-finding work of a judge usually involves a series of cerebral operations, some simple, others complex, some sequential, others simultaneous. It can be frustrating and excruciatingly difficult. With the move to remote hearings via videoconferencing technologies, judges are now in an informational environment that is more intensive, more extensive and less controllable than it was in the past with far reaching consequences on participants.

For instance, it is argued in Weberian terms that judges’ performance or enactment of their authority in the courtroom reinforces law’s claim to legitimacy and this requires an assurance of procedural fairness, which, in turn, requires a degree of engagement between the judge and other courtroom participants. Remote hearing disrupts this in a number of ways, including that the technology or connection does not always function properly, the video takes away the judge’s ability to assess non-verbal cues and video-conferencing technology can actually filter out frequencies associated with human emotion which are very critical in assessing credibility and reliability. Also, the use of videoconferencing technology in criminal trials could depersonalize the entire process and drastically minimize effective judicial engagement which is one of the hallmarks of therapeutic and problem-solving aspect of judgecraft and frequently deployed in our Gladue, mental health and drug treatment courts. During sentencing, judges employ a range of communication strategies to achieve legitimacy such as directing their gaze and speech directly to the accused person to create ‘a more engaged, personal encounter’. This communication strategies employed by judges are usually deployed to address offending behaviours in drug addiction, houselessness and mental health cases. Anleu and Mack, and Wallace et al.,

argue that judges require a more relationship approach to judicial work and judges make greater use of their personal and interactional skills to secure more effective sentencing outcomes. What is currently left in any criminal court proceeding is a computer interface showing the head and shoulder shots of the judge, the crown attorney, the defence counsel, the members of the jury and the accused persons are shown with no meaningful engagement between the participants. Due to the lack of bodily co-presence and full sensory engagement with remote hearings, most participants including judges feel “depersonalized” and as a “less human experience” “less humane”. In fact, an Australian judge emphasized the importance, for them, that all litigants came together in one place, as a reminder of the “human condition” and that the difficult decisions being made in court are not undertaken lightly or flippantly.

The judge believed that those sentiments were difficult to convey to a person appearing remotely. In a virtual hearing, the typical court “atmosphere” - which is very important in conveying solemnity and framing the judge as legitimate and authoritative, and the spatial distances between all the court participants, evaporates. I will now turn my attention to what happens when we lose the structure of the court. The notion of “court atmosphere” is also called “affective atmospheres” which

means the assemblage of affects, that both the material and human give cause to, and reproduce. It is used to explore collective affective qualities that are perceivable as they emerge between bodies and their environment. This ‘affective atmospheres’ are usually materially crafted in physical courtrooms, and engineered through the material arrangements of the courtroom.

Philippopoulos-Mihalopoulos argued in his book that there can be neither law nor justice that are not articulated through and in space. What this argument highlight is that court architectural designs provide the spatial arrangement for the engineering and crafting of the affective atmospheres which communicates community values and the important of the maintenance of the law and order in the Canadian society. The interior arrangements and aesthetical layout of the courtrooms create resonance between the physical bodies, provide judges control over the situations and at the same time project the visual and material representations of law in operation. The physical courtroom arrangement also cue particular type of behaviours to encourage participants to conform to the norms of the legal ritual occurring. These cues have been described as the coercive power of the courtroom and the judge as defiant behaviour by participants could lead to a charge of being held “in contempt of court”. Participants participating in court proceeding via videoconferencing technology lose the “affective atmospheres’ of solemnity, respect, deference and the formality of a courtroom, and in turn the judge loses the authority and power of disciplining erring participants far from the physical reach of the judge.

In fact, some judges reported that some litigants were unruly while remotely participating in court proceedings, emboldened by the fact that they are not in the same room as the judge and are on their own territory, as such they don’t have to be told what to do or how to act in their own environment. Remote hearings reconfigure the encounters in the courtrooms and remodified the relation between law and the people subject to it. While embracing the virtual hearing environment could be seen as an easy solution to making the “court atmosphere” less daunting and easily accessible to vulnerable people, minors and first-time users of the court system, it might actually have unintended consequences. For instance, a study conducted in Australia revealed that interviewees indicated that the video links fundamentally disturbed courtroom interactions and its rituals with these interviewees less comfortable with their experience overall. Another Australian study on remote hearing suggests that the use of video links “alters the representation of the judge as the embodiment of law, weakening symbolic and cultural dimensions and undermining the gravity and decorum of court proceedings”. Most participants miss the “display of justice in practice”; the respectful and solemn atmosphere and behavioural cues conveyed by the impressive architectural designs of court are lost.

While the use of videoconferencing technology opens up the traditional courtroom to multiple, simultaneous and interactive sites of adjudication and provide broader access to the public, yet studies have shown that participants in court proceeding through the video conferencing technology most often find themselves in spaces that could be characterized as bland, ordinary and mundane. Studies found that accused persons who participated in remote hearings found the judicial process as less legitimate with them less likely to have legal representation as they do not take the entire process very seriously and therefore have negative impact on outcome for them. A September 2020 report issued by the Law Society of England and Wales raised significant concerns that a mere 16% of solicitors polled reported that vulnerable clients were able to effectively participate in remote hearings. In situations where clients had no particular markers of vulnerability, 45% of solicitors reported that they were able to participate effectively. The report also indicated that “people who do not communicate regularly [via phone and or video conferencing] find the experience very disconcerting and struggled to follow what is in an already unfamiliar legal process and find it difficult to adequately present their case. Body language and signs of distress can’t be picked up on as easily.”

I will now turn my attention to the impact on open court principle and judgecraft One of the significant impacts of remote hearing is redefining the concepts of open justice which play a critical role in the court carrying out important adjudication functions involving the exercise of judicial power and giving legitimacy to our judges. Throughout the years, in the pursuit of open justice, evidentiary hearings and trials are generally live events conducted in a dedicated physical space accessible to the members of the public, the press and court watchers with the goal of ensuring just procedures and outcomes for all the participants. The “liveness”, “momentousness”, and the visibility of hearings and trials are what metaphorically makes the courtroom a stage and the trial as theatre which is always notionally part of the spectacle of performance that our judges engages in every day. It also serves as a reminder that judicial proceedings are not merely private interchange, but an important function performed on behalf of the community, in which community-wide problems are addressed and norms are articulated.

For Thurman Arnold, a public trial, particularly a criminal trial, “represents the dignity of the state as the enforcer of law and at the same time the dignity of the individual even though he be an avowed opponent of the state.” Like other common and civil law jurisdictions, the open court principle is a key bedrock of our judicial system as enshrined in the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms and ensures that public confidence in the integrity of the court system and the ideal that the administration of justice is promoted by openness and full publicity. The Supreme Court of Canada held that the “open court principle” is a “hallmark of democratic society” that “gains importance from its clear association with free expression protected by s. 2(b) of the Charter.” The move to remote hearings raises the important questions: “where’s the court located? Whose right is the right to a public trial? What precisely is the role of the public in securing this right? These questions are very important as it is very crucial for the community to know where to go to see justice being dispensed, the need for a court to be easily located by the public for them to readily view proceedings – which are the hallmarks of the open court principles. A major criticism of remote hearing via videoconferencing technology is that it restricts public access to judicial proceedings and breaches the open court principle. An opposing argument is that court proceedings can be broadcasted to the public through technology platforms such as YouTube and that it will satisfy the open court principle.

It is further argued that the public gallery in our courtrooms is typically not utilized by spectators on a daily basis so the impact of moving judicial proceedings online and broadcasting through YouTube is not detrimental to the open court principle. So, the “virtual presence outweighs its urban presence”. To address this issue of open court principle in light of COVID-19, for instance the Ontario Court of Justice issued a Notice regarding public and Media Access to Judicial Proceedings, the court acknowledged that there might be restriction to the public participating in the judicial proceedings could be limited due to technical limitations, legislation, publication ban or court order. But in other cases, members of public and members of the media who are interested in observing proceedings can email the respective court houses to obtain access details. The notice did not indicate that judicial proceedings will be live streamed. As it is currently structured, obtaining access details is not user friendly and directly undercut the well-entrenched idea that one can just stroll into a courtroom without having to make an appointment or turned away at the door by security. This throws up a critical question: is it acceptable for some participants to access the court proceeding remotely, why not the general public? I will now turn my attention to the aspect of judgecraft.

Exercising adequate judgecraft with the use of videoconferencing technology is very important in achieving temporal goals and can further create space for a more engaged and legitimate decision-making process in Canadian criminal court. Judgecraft is a a practical craft and is firmly bounded with the legitimacy of judicial authority. Based on the relational concept of procedural justice, the legitimacy of judicial authority is bolstered in part to the extent to which courtroom participants perceive that they are treated fairly by the judges they encounter.

What this means is that there is a need for more active engagement by judges in our criminal courts, but this could at the same time runs contrary to the adversarial norms which requires a formally passive judicial role with more active roles for other participants. On a personal observation of court proceedings in some Ontario criminal courts I found that video hearings require additional judgecraft to effectively manage the hearing and maintain their authority. It was difficult for judges to manage participants’ reactions and participants are more likely to talk over one another due to the lack of physical cues around turn-taking.

It requires extra time to use formal turn-taking cues that might otherwise be picked up visually or intuitively in a physical hearing. Participants including vulnerable persons are more likely to go off on a tangent and it was more difficult to get participants on track via video hearing unlike when they are in the same physical space. Another concern includes the ability of a judge to determine if the parties are following the proceeding through video hearing. Due to increasing caseload in criminal courts and need to the meet the presumptive ceilings for the completion of trials as established by the Supreme Court of Canada in R v. Jordan,

there could be heightened time pressures in lower criminal courts to quickly complete cases and this creates additional problems with actively managing multiple tasks, and the unpredictability of the criminal list for judges. With the move to video hearing, these problems are now more acute and challenges the ability of judges to create sufficient time and attention for active engagement required by procedural fairness values which underpin legitimate judicial authority. In general, video hearings are more draining, stressful and tiring for judges, especially those in the mental health and drug addiction courts, as significant amount of time is spent on establishing sufficient technical connections for all the participants. I will now speak specifically on the displacement of community values. A crucial issue is if the use of videoconferencing technology for the purposes of remote hearing adequately convey to court participants a sense that the judge is dispensing justice on behalf of the community and in accordance with its values. The tangibility of that community through proximity to other community members is visibly absent through remote proceedings.

For instance, Judges in the UK had mixed feedback about the formality of video hearings, the way their authority was perceived, the challenge of maintaining authority and a formal atmosphere without the physical cues of a live courtroom. Most judges felt that it would be useful to have a court seal included in the video hearing to remind participants of the authority of the judges to dispense justice on behalf of the community. This throws up several issues. For instance, if an accused person being sentenced by a judge do not have a sense of being in courtroom setting, it may also mean that they do not recognize that they are participating in a group- performed ritual with a long tradition that is enforcing the community values of the society. In turn this alter the perceptions that all participants have of both the outcome and the process. I argue that the need for a judge

to feel that the values they are enforcing are those of the community they represent and serve, and it reflects the “chain legitimatization” that authorizes the judge to adjudicate the dispute. When the judge loses the community-context of their work as typified in a traditional courtroom, there is that anxiety and fear that the adjudication and any judgment issued will be perceived as an arbitrary act of violence against the accused person. The fear is that moving the court room entirely remote, participants may fail to perceive the court and the judge as legitimate and authoritative.

This fear is legitimate as studies in the UK found that accused persons who appeared by video saw the process as less legitimate and were less likely to have legal representation. This failure to obtain legal advice and representation may be linked to an accused person’s diminished ability to effectively present their case resulting in worst outcome for them. In my talk today, I demonstrates that judicial architecture and rituals play an important role in legitimizing the Canadian criminal justice system. As there is a continued scale up in the use of the videoconferencing technologies to conduct remote hearings in our criminal courts, it is very important not to ask the question: “what do we have to gain or lose from adopting videoconferencing technology”, rather what we should be asking ourselves is the important question of “how best do we use videoconferencing technology in a way that corresponds to our fundamental legal principles, project the right image of our judges and promote their legitimacy as the custodians of our community values? Over the years, sociologists have suggested that the perception of legitimacy and due process are impacted by the space of law and people's encounter with it.

Therefore, it is safe to argue that the success of the increasing use of videoconferencing technology in our criminal court is contingent on the existing symbolic functions of the physical courthouse and the rituals not lost but being identified and reimagined. Our that total disposition over to discuss on, and I look forward to a rich discussion of some of the ideas that are activated in this discussion Thank you everyone. Thank you, Dr Akenroye Yes, okay great you've shared your, so I will also put my video on the PowerPoint is no longer there, so thank you, so let me just move things along, then we have to discuss today. And so much to talk about I mean in your presentation there's certainly a tension between, on one hand, questions of legitimacy and authority of the judge, on the other hand, and the extent to which space and the place of the courthouse is essential to that, on the other hand. You know people's relationship to this new modality and the implications for this this sense of authority and. You know their their larger questions about

the extent to which even prior to covert 19 to what extent very good authority or whether or not it's it's always deserved in in all cases. And so clearly you're doing a deconstruction of ritual and pushing us to think about judge craft as the particular kind of production of authority and its implications in this new situation, but they're there, I think a lot of unresolved and fascinating as well as Probably controversial issues at play here and and your experience as as, certainly in the role of a judge, as well as in your capacity as a lawyer. Certainly shed light on some of your initial thoughts, as well as the data you've collected, thus far, so thank you For that, and I think it's really time for us now to roll up our sleeves and take on some of the very forceful arguments, but I suspect that will also have some disagreements on on that, so we welcome that as well, so that our first discussed it is Anne Marie more for, and I have the pleasure of introducing her. She’s a principal lawyer at Morphew

Symes Barristers. She obtained her law degree at the University of Ottawa, where she graduated magna cum laude with her J.D. in 2011. While at law school, Anne Marie was awarded numerous academic and oral advocacy prizes, including prizes for the highest grades in several law school courses. She was called to the Bar in Ontario in 2012. Her practice focuses on complex criminal trials and appeals. Anne Marie believes that being the most prepared person in the courtroom wins trials and she approaches every case with that mentality.

She has conducted numerous homicide, complex fraud, gun, drug, sexual assault, and impaired driving trials and regularly appears before all levels of court in Ontario. And it's really a pleasure to have her with us today and to serve as the first discussant our second before we before she comes on, let me also introduce our second discussant Wumi Asubiaro Dada who is a Ph.D student in Criminology and Sociolegal studies at the University of Toronto where she is working on a dissertation project related to the complexity of choice and agency of female combatants within Boko Haram insurgents in Nigeria She is also a human rights lawyer with decades of experience working on issues related to social inequality, gender-based violence, women’s political participation and legislative advocacy. She received a Bachelor of Laws degree from Lagos State University, Nigeria in 1999 and was called to the Nigerian Bar in 2000 having completed her Law School in Nigeria. She completed a Master of Law Degree with specialisation in human rights and democratisation from the University of Pretoria in South Africa. And she has worked in law and public policy for the past 19 years where she has designed and managed projects on women and legal reform and She has contributed to significant projects connected to gender and led national research surveys and done significant advocacy work so both as a scholar, and as an activist she to will bring an interesting perspective, as she reflect on on the top so without further ado, then let's invite Annemarie to join us first and then we'll just move straight into Wumi’s presentation, thank you. Thank you so as indicated I practice criminal law,

I do quite a bit of trial work in mostly serious cases, which certainly impacts sort of my view in terms of attending court in person or participating in virtual or remote hearing, certainly, since the start of coven 19 in the courts reliance on video technology. I have participated in a number of guilty pleas and sentencing hearings various motions and appeal, as well as many case management appearances. I haven't participated in a trial with witnesses and the Cross examination of witnesses by video but certainly there's been much discussion with the Defense bar Over the appropriateness and the limits that should be placed on moving to virtual and digital hearings and I can certainly indicate there's Quite clearly, a divide, even within the Defense bar about the appropriate cases and how we ought to be moving forward using digital and video Court appearances, because it's quite clear they're here to stay, and so I do think that number of the points that have been raised today and in the paper are quite important, in deciding and sort of determining how best we move forward to ensure that the Court maintains both its legitimacy to the broader public but certainly to the parties the accuse the witnesses, the complainant send the victims and their family and friends and I will indicate when we when we talk sort of practically and I’d like to offer some more practical and sort of personal insights into how video courts have been conducted and the issues that arise within them, but certainly there's there needs to be a recognition that what a video hearing or a video court looks like even within Ontario differs greatly between the jurisdiction that you're in terms of the courthouse the level of the core. But even sometimes within the actual courthouse depending on the specific court room your mater is assigned to the manner in which the technology is available, the manner in which it works and what is actually visible on the screen during a virtual hearing differs quite significantly and so depending on that you see a number of different issues that arise, sometimes in certain cases that aren't in others.

And I think, for me, certainly as a defense lawyer, the starting point in criminal law is that there needs to be a recognition that criminal law and in the court process it's a very important and a very significant event for those involved being charged with a crime has the potential to be life changing and life altering for that person and their family. Being the victim of a crime or even witnessing a crime also brings with it the possibility of being quite life altering. To those people and their family and friends and so it's From that starting point that I think moving forward the courts and the participants me to ensure that these individuals who participate in the hearing, are also receiving a fair hearing and justice. As a defense lawyer my focus is usually on the accused or my client, as opposed to sometimes more broader concerns but certainly I view my job as not only to help my client in obtaining a favorable outcome but to ensure my client not only receives a fair trial and adjust results, but the he or she walks away from the proceeding feeling themselves that they received a fair trial and a just result. And built within that and ensuring that we give that to those accused people is our adversarial system which centered around having an independent, excuse me an impartial decision maker, which is again part of the constitutional rights that we have provided to accuse people.

And so, where we see the image or the authority of the judge as that independent and impartial decision maker being altered or being eroded, I do think that there are constitutional implications with respect to the right to a fair trial, as well as ensuring the participants themselves feel that justice is being done. And so I want to start, I do have some comments, some of them sort of examples of where we see based on the appearance of the proceedings once we've removed them from the courthouse and the Court rooms that certainly raised some of these concerns that have been discussed today. And again, I think they're related to the erosion, or the lack of sort of personalization of a case of the of the justice system, as well as how the Court is able to personally engage with those in a particular case that are the be involved parties as opposed to the broader public.

And for me, one of the features of not only the courthouse but a court room is that is a place where justice is done but we're justice is open in least in theory to all it is available for all, in theory, the courthouse and the Court room provides an equal opportunity for people to avail themselves of the justice system. And it's the court with the judge at the helm that aims to treat all those who come before it with dignity and respect in an equal manner. And what that to me sort of symbolizes or focuses on is that whether you're rich whether you're poor whether you're on bail or if you're in custody.

If you're white if you're black if you're indigenous that you can come to the same building and literally the same building the same room, with the same judge and receive access to Justice, whereas with digital and virtual hearings this equalization or this equalizing effect of the courthouse is diminished and it's diminished in particular to certain groups of people and of course the first would be the indigent accused or parties who simply don't have the ability to access digital proceeding. With the speed at which Ontario has attempted to move towards virtual and video conferencing hearings there doesn't seem to have been significant amount of thought put into what happens to those accused who are not able to access zoom or video conferencing systems to participate in court. And we see it continually arising I see it in my own clients who are either experiencing homelessness or don't have a smartphone their flip phone doesn't allow for the zoom app. I also see it continuously and remote communities where the Internet simply isn't strong enough isn't reliable enough to be participating in court and also just in more rural areas where, again, there are issues with the Internet and the availability.

And whether it's the Internet cutting in and out such that the person isn't actually following the proceedings because they are not hearing them. The Internet not working at all. Or what tends to then happen, the response is that the accused cannot connect to video is told that they can just call into a teleconference number and participate in that way. Which in which they would not be on the video, they would not see other people and they're not seen.

And what we then do at that point is we've taken at least one party one member of the court proceeding and we've put them into a different category we've made them different, they are no longer equal they are no longer on an equal playing field in which to participate in the hearing and, in my view, were diminishing their role, their ability to engage in the proceeding and making it less personalized as the judge is not able to see that individual to have any sort of engagement, or contact with. And related to that are the accused people who, not just who don't have the technology, but those who aren't necessarily comfortable with the technology and we sort of see that similar ways in which the focus of the hearing them becomes on whether they're following along are they still connected and they're focused on well, am I doing everything right, am I doing something wrong and they're not been focused on what's happening or on what the judge himself or herself is doing. And, of course, within these groups of people who don't necessarily have the same ability to connect we see again that it's typically, and not always but sort of typically the same groups of people who are already vulnerable and are already discriminated against in the criminal justice system whether by the police and their charging practices or just generally once they come into court system. And so I do think it's important moving forward that something is done some consideration is done to how we return these vulnerable people to an equal playing field into an equal standing in remote hearings. Additionally, setting aside those out of custody who don't have the ability, there are a number of concerns I continually see with in-custody accused people being brought to virtual hearings.

If they're brought, it's been my experience, to a video conference court appearance, they don't leave the institution they don't leave the jail, which means they're often participating in court wearing their orange jumpsuit, their jail issue clothing, and at times they're sort of last in this small tiny room without those full comfortable ability to participate in their own hearing. Whereas if they were brought to an in person appearance or trial, they would be given the opportunity to change into not only their own clothes, but their clothes that would be appropriate for court that would allow them to be comfortable and to participate with a level of dignity and respect. And it's the judge in those situations, who is in charge, and has that authority to ensure in custody accused are being treated with dignity and respect and are able to appropriately participate in their own hearings and they're not sort of left in this room to awkwardly stand there for two hours, while everyone else just talks about them. And while these issues are sometimes address on an individual basis, case by case, depending on the lawyers and the judge, certainly it's something that, as a broader issue going forward, we need to ensure that these people in these vulnerable groups are in custody who again we know tend to be racialized and that we're over incarcerating indigenous accused as well as Black accused at a staggering rate.

That there again brought into this equal playing field in which to access justice and in which go before a judge and have that person truly be the person in charge, and the person who, through their authority and the respect they command and the room is in charge of the proceedings. And maybe just the last point on this that I’ll add is in specific with respect to the judge. With the increase in virtual and video conferencing hearings it’s been my experience that the judge has become much more reliant on other people and other parties such that it has the ability, certainly at least appear to be eroding their authoritative position in the hearing. The judge often no longer has the paperwork it's all with the Clerk so the judge is reliant on the Clerk or the Crown to get any information about the case. what's on the docket for that day what's going on with the cases and when all the technological issues arise which they always do the judges never in a position to fix them or just send out instructions about what then happens the judges always reliant upon other people to come and or figure out the issue and to fix it. And some of that, of course, is just a an issue with resources, but again within custody people we've reached a point in many jurisdictions in Ontario where the jails literally run the show, the jail will send out to the court the schedule for the day indicating this is when you'll hear this matter, this is when you'll hear this matter because those are the only times, we will produce that accused person who's in our custody to appear before the court and on many occasions, it leads to the jail either not bringing people to court or literally hanging up the phone or disconnecting the video when they want to move on to something else, despite the judge saying we're not done

2021-02-04 07:44