The Truth Machines

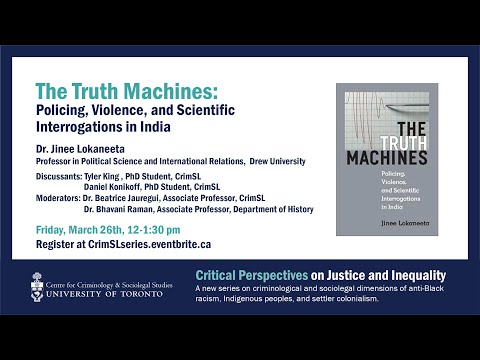

Today we are delighted to welcome Janee Lokaneeta who is Professor in political science and international relations at Drew University in New Jersey. Professor Lokaneeta's areas of interest include law and violence, critical political and legal theory, human rights and interdisciplinary legal studies and her recent book, which we will be discussing today titled The Truth Machines: Policing, Violence, and Scientific Interrogations in India theorizes the relationship between state power and legal violence by focusing on the intersection of law, science and policing through an ethnographic study of forensic techniques, that is narco-analysis brain scans and lie detectors. Janee is also the author of Transnational Torture: Law, Violence, and State Power in the United States and India published by New York University Press as well as Oriental Black Swan, and the co-editor with Nivedita Menon and Sadhna Arya of Feminist Politics: Struggles and Issues. So I’ll now introduce some of the other co-panelists that will be here today with the discussion. I myself I’m Beatrice Jauregui I am Associate Professor here at the Centre for Criminology and Sociolegal Studies and I am joined in co-moderating this discussion by Bhavani Raman who's Associate Professor of history at UTSC, Scarborough campus of University of Toronto. We will have two PhD students from the Centre for Criminology and Sociolegal Studies discussing Janee Lokaneeta's book.

Daniel Konikoff is a third year PhD student at the Centre and a graduate fellow at the Schwartz Reisman Institute for Technology and Society. Daniel is interested in the intersection of criminology and science and technology studies, or STS, with an emphasis on police technologies, big data surveillance and predictive justice. Also discussing Professor Lokaneeta's book is Tyler King, who is also a third year PhD student here at the Centre and his research focuses on the presentation of expert testimony and diagnostic technologies in criminal trials.

So I thank everyone for coming today and to start us off we will have Janee Lokaneeta herself give us a bit of background and context on her book The Truth Machines: Policing, Violence, and Scientific Interrogations in India. Thank you, Janee and please go ahead. Thank you thanks so much Professor Beatrice Jauregui for the introduction and to you and Professor Bhavani Raman for inviting me to University of Toronto, which I wish I could have done in person.

One of my favorite cities with some of my favorite people but I’m happy to be in the Zoom room with you all so, and thanks so much to Daniel and Tyler for agreeing to be discussing. So I’m in my brief remarks let me contextualize my research a bit may present a few themes from The Truth Machines and I look forward to the discussion my research focus as was just mentioned has generally been on the relationship between law, violence and state power in liberal democracies. In my previous book, Transnational Torture, focusing on India and US, I traced how jurisprudence that is considered the most legitimate state discourse formally condemns torture yet ends up accommodating excess violence in that book I primarily focused on analyzing legal cases from both US and India, reports and cultural representations of torture in TV shows like 24 to intervene in a debate on whether torture was an exception in liberal democracies and argued that excess violence was very much a part of the governing in liberal democracies. In The Truth Machines I shifted from jurisprudence to examining more closely state actors who are responsible for interpreting and implementing the laws and safeguards against torture. Torture is pervasive in India in many different contexts. In routine theft cases mostly against those who are marginalized on the basis of caste, gender, sexuality, class and religion for instance.

In terrorism cases using stringent anti-terror laws, which have a long history in India from colonial times or in so-called conflict areas Kashmir or parts of northeast with laws such as Armed Forces Special Powers Act and now increasingly seen against protesters and activists under extraordinary laws like unlawful activities prevention act and sedition laws. So this was most recently seen in the farmers’ protests where Dalit activists like Nodeep Kaur and Shiv Kumar were arrested because of their role in supporting workers struggles for wages that were withheld during the pandemic and for their solidarity with the farmers’ movements which is which has been going on in India and both activists were tortured in custody according to doctors reports. If these are the contexts in which torture exists in India the puzzle in my book that I started off with is why in a context where torture exists with such impunity and officials are rarely charged or convicted a discourse on truth machines to replace physical torture appeared and how does it help us understand the relationship between state power and legal violence in liberal democracies. So in addition to focusing on legal cases reports political discourses and popular representations, I conducted interviews with police, forensic psychologists, lawyers and activists in five cities, Delhi, Hyderabad, Mumbai, Bangalore and Gandhinagar to understand the relationship between law science and policing. I focused on the emergence of three scientific techniques that at term truth machines narco analysis, which is the injecting of sodium pentothal for inducing confessions or information or popularly called the truth serum, brain fingerprinting and brain electrical oscillation signature test that supposedly captures experiential participation in a crime through an electroencephalogram and lie detectors that measure physiological indicators.

The popularity of these three tests can be seen most recently in their mentioned and used in the horrific gang rape and murder case of a Dalit woman in Hathras Uttar Pradesh in northern India a few months ago, but also in other cases. In fact on Delhi High Court insistence, the Delhi government has just announced this week that it has set up a narco facility, narco analysis facility, in Delhi to prevent the need to travel elsewhere. My focus is to study and understand the everyday practices of the state not captured by more monolithic conceptions of the state whether it's a more Weberian bureaucratic conception of monopoly over legitimate violence constrained by rules or a more Agamben inspired understanding of a sovereign state's violence over bare life, here I draw more from the anthropologists of the state and adopt a more ethnographic sensibility I put forward the idea of a contingent state which refers to the ways states constantly oscillate between the desire to be unitary and the inability to do so under certain conditions. The concept of contingent state points to the continually negotiated nature of the relationship between state power and legal violence. For instance, if we just see the emergence of these techniques it's both a story of a disaggregated arbitrariness on one hand and state intentionality on the other. There is often an assumption of clear intentionality in state techniques.

For instance think of changes in methods of executions in the US, from hanging to lethal injections that Austin Sarat writes about, or from scarring to non-scarring torture techniques as Darius Rejali notes. The rise of these particular truth machines were actually the result of some ambitious forensic psychologists in forensic science labs in Gandhinagar and Bangalore wanting to gain visibility, legally and in public, that actually led to the popularization of these techniques. But the truth machines also fitted the postcolonial state's desire to appear as using scientific and modern techniques in part due to the critique of the human rights movement that was consolidating in the 1980s and 90s.

It was primarily in the post-1975-77 period after the Indian emergency that was imposed by Indira Gandhi due to internal security reasons that the human rights movement really started consolidating in India. And both due to internal and external pressures India set up a national human rights commission that focused on custodial deaths though did not acknowledge the role of torture in custodial deaths. The argument was often that torture was a result of illnesses and suicides in official reports until a few years ago. The 1990s also is a period when the Supreme Court jurisprudence on torture like the DK Basu case also emerged. It is at this time that the aspirations of the individual forensic psychologists seem to merge with the need of a postcolonial state to use science and expertise to find technical solutions for police torture.

In some ways it's similar to what Timothy Mitchell calls the techno politics in the context of Egypt. An alloy of non-human and human or what I called an attempt on the part of primarily female forensic psychologists to be a cyborg of sorts, a combination of scientific machines and use of therapeutic art to be distinguished from the quote unquote brutal police. However the ills of the Indian criminal justice system were to be addressed by the developmental estate to create a state forensic architecture that is with machines and experts with no regard for reliability or validity of these techniques or their coercive aspects. In fact the state high courts in mid-2000s basically welcomed the techniques as replacing the physical torture by involving medics and as a natural investigation, sorry, natural extension of the investigation. Considered safe, representing modernization similar to other life-saving machines like MRIs, the supreme court even when it intervened in 2010 focused on consent and allowed for exceptions in terms of admissibility of evidence as a result of these.

In the process even the highest court doesn't question the paradigm itself of using questionable signs of allowing medical professionals who had played an uneven role against torture in the past and doesn't completely challenge conditions of police custody or remand which is often seen as synonymous with torture. It's also important to note that both lie detectors and narco analysis have a long history in the US and brain fingerprinting a more recent innovation even as their reliability and validity was always in doubt especially for legal purposes. Yet their persistence often remains in the realm of the popular than necessarily legal. Now in the Indian context the truth machines didn't of course actually replace physical daughter because they got used in either very few cases are themselves coercive and they often got used alongside physical torture for terrorism related cases in order to get particular answers. So as a Muslim male detainee in the Makkah masjid case of 2007 said about a forensic psychologist and I quote she slapped me strongly and started pinching my left ear with pliers because of which I suffered more she asked me many such illogical questions and used to ask me to repeat the answers if I did not give the expected answers, both tortured me badly during the narco test end quote.

The concept of contingent state then helps us think about the role of other actors involved in policing. The forensic psychologists who claim that they are different from the police and provide therapy as an extension of the of the machine. As one psychologist said and I quote while torture is an external stimuli these techniques are internal ones and invite an internal journey. They force you to review your past in a different way not, confess but ask them to think about themselves and come back. It is a moment of catharsis in the legal system.

Unlike the police custody where there is fear of encounter or custodial death or torture here there is empathy end quote. In the Mumbai blast case of 2006 Abdul Wahid Shaikh, the only one acquitted and an activist and lawyer now for the Innocence Project also initially believed that the truth machines conducted by the doctors would reveal the truth about his innocence until he realized it wasn't to be. The psychologist even claimed that the techniques won't actually work if the persons are physically or psychologically harmed, gesturing to a shift in the mode of interrogations. But then they end up creating the same conditions in labs and hospital that prop up physical torture by utilizing these coercive machines to get confessions involuntarily and therefore need to be squarely rejected. But the management of this violence and the actors beyond the police are important to recognize in the disaggregated and multifaceted form.

Finally the contingent state helps capture the experience of those impacted by the violence that has points of intersections with the police accounts. In the two terrorism related cases which focus entirely on Muslim men, many state, semi-state actors such as the medical professionals and magistrates helped hide torture of Muslim men creating a kind of a scaffold of a rule of law. The idea of the scaffold is that that the very procedures that are meant to be safeguards against torture right within the law to be brought in front of a magistrate or subject to a medical examination often become just bureaucratic check marks that end up hiding the violence. The procedures are technically followed thereby preserving the scaffold of the rule of law but ends up masking not revealing the state violence.

This is something that happened even with the father-son duo Jeyaraj and Bennix who were tortured and killed in custody in Tamil Nadu in Ja- in June that prompted much outrage, echoing the George Floyd and Breonna Taylor protests in the US. Yet Sheikh, Abdul Wahid Sheikh, in his powerful book Begunah Qaidi also reveals what the police are constrained by. A police, a dead body in custody. And I quote first in Hindi, [Hindi uncaptioned] [17:28] But you should remember that the police will not kill you with the dodger they will only beat you to the extent that you agree to do their work the police won't beat you in such a way that there are physical wounds.

This sentiment is echoed by a police officer in a training academy who connected the human rights movement, the NHRC reports national human rights commission reports, and the DK Basu supreme court case. These he believed collectively made the police much more nervous about deaths in custody. I quote him: The suspect's safety is in your custody you don't want him to die so you take care of him, your brother, you're scared of death, end quote. Often the Indian police is understood either as a colonial continuity or inspired by a more Marxist conception as a repressive institution of the state and these insights as a result are less revealed and in this limited sense drawing from new police studies scholars, I term the termite the pastoral role of the police mediating the coercive I point to how studying the police as a site of state power in the everyday sense allows for an access into the structural constraints of the police but above all reveals in their own words the pragmatic logic of why third degree continues. It is the fear of the custodial death that has allowed for the mediation of the coercive with the pastoral. The emergence of these truth machines does help one understand the vacillations of the contingent state and whether there are shifts and cracks possible in both the narratives and practices of the state that above all have life and death consequences for those who experience state violence.

It also reminds you then of the need to focus specifically on the constantly negotiated relationship between state power and legal violence as central to our study of police and state. While state has been studied and violence as well I suggest the need for state violence studies at this moment. Thank you.

Thank you so much Janee. It is a very very powerful book and I think we can see how relevant it will continue to be, unfortunately. So I am now going to ask the first of our discussants, I’m just going to go in alphabetical order by last name, so Tyler King who I’ll just reintroduce in case you joined us late, is a PhD student here at the University of Toronto Centre for Criminology and Sociolegal Studies whose research focuses on the presentation of expert testimony and diagnostic technologies in criminal trials.

Tyler. Thanks a lot Beatrice and sorry Daniel I know we spoke and I said you can go first but I guess I beat you by a couple letters. It's totally okay. Yeah sure I can go first and of course I’d like to start by thanking Beatrice for inviting me to speak today and of course to Professor Lokaneeta for allowing me to comment on what we just saw is clearly a profound and important work.

And I guess where to start is just I’d like to point out that this was a very enjoyable book for me to read for multiple reasons and first and foremost I’ve quite recently shifted from talking about you know more traditional criminological theory into the science and technology studies world and I’ve noticed just how impossible a lot of STS scholarship is and this book was not that in the sense that it was theoretically dense but stylistically very accessible so that was refreshing so I appreciate the stylistic choices you used, including very liberal usage of verbatim quotes from your interview subjects, which were super helpful and the other reason why I love this book is because it merges sort of three themes that have been prominent in my own life and I sort of viewed them as quite disparate but I’m now thanks to your work starting to see that maybe there's more link between them than I thought and so the first sort of theme is you know throughout my childhood, I was in the army cadets and then when I was 19 I joined the real Canadian Armed Forces, very briefly, it was a dark period of my life, but I got a close-up look at state violence in the broad institutional sense and I’m not on the army's payroll or anything but I should say I didn't notice any overt practices that we think of as classically torture but that said, as we know, violence isn't always classically physical and honestly boot camp was sort of torturous for me but that's another story. Then in my 20s I became a licensed private investigator so I have some first-hand experience with the investigative techniques and policing strategies that you mentioned, although like your forensic psychologist in your book, you know, I’d be considered a sort of non-state or at the most semi-state actor as we don't really have strong relationship relationships with the police and often we're going up against them in court, but a lot of the techniques are the same and I think that's important. And then finally, where I am now in my life in my 30s, I’m now researching the role of expert testimony and diagnostic technologies, specifically brain scans, on criminal trials. So I never really thought of these things as related but when we start looking at grand narratives and theories of the state in its broadest sense, there probably is more linkage than I originally gave a credit for. So that was a long about me. Anyways what do I want to actually focus on in my short time related to this work so there's two themes that I kind of want to speak on and the first is more science and technology studies related and the other which is more substantive is more related to your discussion of the theory of state, which really is what the book is about, it's not a critique of these three truth machine methods per se, but you know the way I read it is it's more of a critique about what these methods say about the state and state power.

so first the sort of main STS point, which as I’m speaking I’m realizing is actually sort of methodological, is I wonder if it would help to separate a critique of the truth machines from a critique about what experts say about the machines or their results. So on the one hand we can critique the machines themselves and how accurate they are, you know whether they're scientifically valid, but I think there's also a critique that maybe we should keep separate and distinct which is about you know how the experts present that data or what they say about the validity of the machines. Because those things can be obviously very different. You know a machine might have a known error rate and in fact I can't imagine a machine or technique that wouldn't have some type of error rate. But that doesn't mean an expert won't present that machine or that data as infallible or definite even though after a seconds pause you know that that's impossible. So if that's kind of where I want to go here quickly is whether there's a value in separating these critiques and a scholar who you cite throughout and whose work I very much enjoy and also follows in in the readable STS camp is Professor Simon Cole, and he has dubbed this separation of what experts say versus the things that they talk about as testimonial fit, which essentially means, you know, can what experts say be supported by the techniques or the machines used to produce some form of evidence.

And of course Cole being the king of fingerprint analysis from a critical perspective uses that in explicating his theory but it's important to note that as he critiques fingerprinting for not being scientifically valid, he's important to note that that doesn't necessarily mean it shouldn't be introduced in court. Because the problem for him I think isn't really in the technique per se but rather it lies in the fact that experts present the technique as scientific when it really isn't. And there are tons of quasi scientific experts that testify about techniques and things that everybody knows, you know, isn't really scientific and there's no problem with that not every piece of evidence can be scientifically valid obviously and even ones that kind of seem scientific aren't and a classic example that Mariana Valverde uses who you also cite is the idea of police officers testifying about whether somebody was drunk or not, is that scientific testimony, is it expert testimony, it's kind of in a very difficult sort of gray area.

Now the problem here I think is that going back to the fingerprint examples experts often come in and say look the fingerprint we found at the crime scene you know is the defendant's fingerprint. That's an impossible statement, it really makes no sense the most an expert could reliably say is that the impression made at the crime scene you know in some form matches the impression taken from the defendant. Now the difference there is subtle but I think it is significant you know provided we know the error rate of that match you know how often false positives are produced. Cole says a technical machine could still have probative value even if it isn't you know classically scientifically valid. Now of course, we don't know the error rates of fingerprint analysis because there's no incentive for fingerprint analysts to produce that data since they're sort of accepted a priori as being valid. But essentially that's I wanted to separate the idea that just because something isn't scientifically valid doesn't mean it necessarily won't have any probative value.

The key is that we need to know, you know, the error rate so that a jury can take a holistic approach and how they want to weigh that evidence. And just this is a quick aside and this is why I actually favor you know critiques of the machines not from a scientific standpoint but actually from a human rights-based standpoint, because as you do so well in chapter four you show how you know something like scientific validity is actually contingent upon things like time and place, so you'll have officials in, you know, Singapore saying that this is scientifically valid and then in different provinces in India people will say no it's not scientifically valid. So even that is you know very dependent on external factors. And so you know that's why I think if we're going to critique these, because if you're someone like me, you don't want them being used, I think you know the more appropriate critique is rather than forcing focusing it on faulty science, it's more on the rights based approach. So in Canada, Charter rights, in the US, I assume it'd be a Fifth Amendment claim, but you would know better, better than I would there.

Now my second point is more relevant I think to the book, because the book isn't a critique of these technologies necessarily, but essentially I want to pick up on what I think is the most monumental thesis and that's the shift from, you know, police and this and the state, from using torture or third degree interrogation practices, to using scientific methods of interrogation, doesn't really represent a shift in governance practices at all. But a quick caveat, I should say that I want to be clear that although it doesn't represent a shift in governance, I think it does represent a difference to the accused person being subject to these practices, I mean if I had to choose one, I think I’d, anything's probably better than physical torture, and that's not a trivial point, because, you know, if less people are dying in police custody because they use science instead of torture then I think that is significant to the people who aren't dying anymore. However the point that I want to make is that, and that you make, I think, is to move away from torture to these new scientific methods doesn't signify, I’m going to go on a limb here and I’m going to say, it what Foucault would term the art of governing.

They are the same types of practices, you know, these torture, third degree interrogation techniques and the scientific interrogation techniques, with the same ends and that's targeted at the body. So in the Foucauldian sense I think these practices are somewhat archaic because, you know, it's a bit of a cliché now, but they are still focused on the body as opposed to what Foucault would call the soul. And this is the classic confessional paradigm that I think you and Foucault outline.

Whereas Foucault says we've moved away from the state simply trying to elicit confessions towards, you know, in modern state practice, towards trying to elicit even the more insidious avowel, which is you know we could also, you know, frame it as moving away from acquiring knowledge about what a person did to trying to acquire knowledge about the kind of person that that someone is or who they are as a person. I think you rightly point out that torture and truth machines, you both outline are modes of inducing confessions but in his work wrongdoing truth-telling Foucault himself says that this isn't any more the ultimate goal of modern justice. You know now we want to get the criminal or the accused to perform an avowal. I mean, not to just admit that they did a certain thing but to admit that they are a kind of person, or at least that's how I understand it, which I always have to throw that that caveat in whenever I talk about Foucault.

So to explain this difference for those who aren't as familiar with Foucault, you know, I might confess to, I don't know, taking drugs, for example, yet I still might not see myself as a criminal or an addict or anything of the sort, you know, even if my admission to taking the drugs counts as a legal confession. But what the modern state really wants to do, I think Foucault would say, is that to get people admit that, you know, not only they took the drugs but that they are criminals or they are drug addicts and the reason why that's so important is because that's sort of the ultimate way of justifying the state's intervention. You say look I am problematic in some way or I am an addict and I need your help or I’m sort of giving you the right now to either force treatment upon me or depending on the crime or how I talk about myself to confine me in some way. But I don't think there's the same express right if you merely confess it, you say yes I took the drugs but I don't think I’m an addict, you know, my drug use isn't problematic for me or anybody else, you can see that that is a narrative that doesn't make the state seem as legitimate there if you're sort of saying yeah okay I did this thing but I don't believe there's anything wrong with it or anything wrong with me. So you know machines that sort of elicit confession I think missed the ultimate goal for Foucault here, which is the next step after the confession, which is to induce an avowal, so for me I think the ultimate, you know, idea of a truth machine would look something like we produced here in Ontario, where I’m located, and that's this idea of drug treatment courts where if you were convicted of a drug crime you could be diverted away from the criminal justice system to treatment programs with no incarceration and possibly no criminal record. But and here's the big avowal part, is that in order to be admitted you had to expressly admit that you were a drug addict, which is to say in order to be eligible for these courts you had to perform an avowal, you literally had to say yes I’m a drug addict, I have a problem if you wanted to be eligible for these programs and I’m taking this from Professor Dawn Moore’s work here, this isn't my own analysis, I should be clear about that.

But a mere confession isn't sufficient to make you a candidate for reform like I said you can say yeah I took the drugs but if you wanna, you know, get that next step and to really justify state intervention, you have to say yeah and I’m an addict ,which is which is a very important sort of leap there. I guess I gotta wrap up now, there's so much I want to talk about because there is it just there's so many theoretical ways you can go here but just quickly I think I’ll say that I think you're absolutely right and that the shift from torture to the three truth machines you outline here isn't really a shift in the art of governing, at least not in the broad Foucauldian sense, because they are both focused on the confession, which in some sense is sort of an antiquated model of intervention based on what the accused did rather than who the accused is. Just quickly actually, I’m thinking now I mean remorse is a great example of that too, the new or the modern sort of reliance on remorse in sentencing where it's sort of absolutely vital now that not only you admit you did the thing but if you want to be, you know, a candidate for rehabilitation, for example, you also have to expressly feel sorry about it and I think that's a brilliant strategy on the part of government because it makes it its laws and intervention seems so legitimate because you're saying yeah I did the thing and I’m so sorry, you're right to punish me for it you know what I did was wrong. I couldn't think of any practice that is more legitimizing for the state in a criminal justice perspective than that and so that's sort of the ultimate form of power in my mind, you know, not just torture, not just truth machines that that act on figuring out what the accused did but, again from a Foucauldian perspective, more on truth machines that sort of focus on who the accused is. So just to wrap up I guess my potential critique or something that I was hoping you could discuss is, you know, I tend to agree as I said with your analysis that, you know, the shift from torture to scientific interrogation isn't really a shift in governance strategies at all, but I wonder if we can make that claim, you know, simply by looking at the investigative stage.

I think it's totally possible that police in a sort of pre and post truth machine era could both be doing the same thing, which is eliciting confessions, but that doesn't mean that the state isn't using those confessions for different ends or for different goals. So you know in the pre truth machine era they might say okay the confession is sufficient to lock you up, you know, but now we have this sort of extra stage where the police still are doing the exact same thing, eliciting confessions but then that confession is being used by the state, you know, to further this new art of governance which is to elicit a vowel so I’m just curious if we zoom out and think about you know criminal justice as a whole practice rather than focusing specifically on, you know, police strategies and interrogation, whether there actually is a shift there, but the shift doesn't exist at the level of policing, it exists on the macro level, so that what the police are doing are being used for different ends even though the practices are sort of the same. I hope that makes sense but anyway those are some of the themes that I was that I was thinking about as I read this and like I said there's a lot more I could discuss but I didn't keep track of time, so I apologize if I went over it, but I will I’ll shut it down there, so thank you very much for allowing me to speak. Thank you Tyler, and we will, of course, give Janee a chance to respond to both discussants but we're going to go ahead with, first with our second discussant who again is Daniel Konikoff, also a PhD student in the Centre for Criminology and Sociolegal Studies, also interested in the intersection of criminology and STS but his emphasis in his own research is more on policing technologies as well as things like predictive justice and big data surveillance.

So Daniel please go ahead. Oh great, thank you so much Bea. Everyone can hear me, okay, everything's fine, okay great. Thank you, Dr Lokaneeta, first for being here with us today to discuss your exciting and informative book, it was really great and I enjoyed reading it, to say the least, I also want to thank Bea for asking me and Tyler to serve as discussants today, for giving us this opportunity to engage with scholarship that at least checks two of my main boxes of interest here as Beatrice mentioned, policing and tech, there's a lot I want to cover and not a whole lot of time to do it and I don't want to take up too much space here, so I think I’m just gonna dive right in with some stray observations and some questions.

So right off the bat the thing that I was struck most by throughout this book was what I guess I can refer to here as the baffling persistence of truth machines. How is it that these tools, which stand on such shaky scientific footing are able to grab hold of police practice to the degree that they do. How is it that these tactics and techniques with questionable scientific validity and equally questionable legal credibility, how are they still in use. So Dr Lokaneeta does a great job of pointing out a guiding principle in Indian jurisprudence, which is this mantra of modernized by any means necessary.

And what surprises me about modernizing by any means necessary is that modernization at least to me really should only hold water if it's synonymous with improvement. Modernization without improvement is something else entirely. And this sort of quest for modernity and innovation is something that also characterizes policing agencies in North America as well as their arcs toward acquiring or implementing and then using newer and newer technologies. So because of the dearth of research surrounding these technologies’ effectiveness it's unclear whether certain technologies actually represent improvements in an empirical sense but they at least, by sheer virtue of adoption and use represent modernization capital m and the imperative to look modern. It makes sense as performative as it may be.

Throughout the book I see Indian courts going back and forth with activists and scholars about the legal admissibility of truth machines results and about the potential harms and negative effects that these machines may bring to bear on an accused and all throughout I see the courts crafting these sort of clever workarounds to ensure that certain legal or ethical concerns about truth machines, like issues of consent or of an accused right to silence or the potential adverse medical reactions that these tests may cause that these courts are going to lengths to make sure that these concerns are addressed. But the thing that sticks out to me is that the courts here are not really wrestling with the fact that these tests are verging on the pseudoscientific and that their police's interrogation regime is built upon this foundation of this questionable science. What the Indian courts and state actors here view as modernizing to me can be construed as at least like technologically regressive, much in the way that buying something because it's shiny and new rather than because it works can be kind of counterproductive. But of course it's totally reasonable to appreciate the appeal of modernity, you know, the silver bullet solution of tech, a misbegotten faith and technology's benefits that blinds us to its ills, or the juicy concept of technological fix that I’m always kind of looking at whenever I’m looking at STS scholarship. So early on, Dr Lokaneeta acknowledges truth machine's mythical status as quote a technical solution for the ills of the criminal justice system, but can something really qualify as a techno technological fix if it doesn't really allow for an actual fix in the first place? How do we make sense of fixes that create new problems essentially, is the big question that I want to ask. As mentioned throughout the book truth machines are kind of designed or are meant to replace or serve as a more humane alternative to third degree interrogation techniques and torture but despite the truth machines usages torture and physical interrogations still happen, existing as what she refers to as a sort of open secret.

So would we be able to qualify truth machines less as technological fixes and more as the sort of ambiguous technological failure hampered by their questionable scientific status and for their inability to eradicate the policing practices that they were meant to replace. And all of my speculation on failure leads me to question expertise, which Tyler touched on a bit as well and I don't want to retread too much of the same ground nor would I, but the way police expertise works here with respect to truth machines, expertise seems to be authority even if that authority is somewhat incorrect. I’m interested in issues like how do these machines become so commonplace when they're scientifically and legally questionable, how can we call the people who advocate for them experts when their expertise is largely contestable, stuff like that, and perhaps most importantly what does this mean for the state in the construction of state authority, when state authority rests on technologies that individuals try to render illegitimate, or that are rendered somewhat illegitimate by their ques- by their scientific fallibility. So moving on I wanted to look next to questions about the interplay between police discretion and police culture. An often discussed component of the literature on policing is that police have their own sort of unflappable culture, that police can be resistant to change that police prioritize experiential knowledge and that they can view ruling or instruction from those outside this stubborn police culture with a fair bit of skepticism. Frequently throughout the book I thought about Indian police culture and what impacts outside court decisions and human rights activism would bear on police, set in the in their ways as they are, truth machines are framed competingly as either an alternative to third degree interrogations and physical torture or according to activists, a sort of continuation of these very violent tactics this brings up questions about discretion and how state power can be can be divided between the police and the courts.

Much of the court's decision making on truth machines, it seems, is about making truth machines more legally acceptable but what safeguards exist to prevent officers from using third-degree torture methods. In reading this book I was struck by the division between police and forensic psychologists. The police are the ones who ultimately make the decision to send the suspect over to the forensic psychologists, who then run the accused through whichever truth machine or machines they seem to, that seem the best fit. But what still seems obscured to me though is how the police make this discretionary decision in the first place and how that might be dictated or limited by police culture.

What motivates police to shuttle an accused off to a forensic psychologist, what barriers of police culture might stand in the way of them making that decision. What is stopping them from continuing to torture or to use their degree interrogation techniques prior to truth machines. So much of what we discuss here has to do with the courts making truth machines acceptable that I couldn't help but wonder whether there exists enough court rhetoric delineating the relationship in itself between police and forensic psychologists. Dr Lokaneeta talks about this in her discussion of legal discourses surrounding whether the courts can create, in her words, quote, an edifice that replaces torture and she also mentions what she refers to as, quote, the supreme court's powerful jurisprudence on custodial violence and routine interrogations.

I’m surprised though by how apparently, what a voice crack, I’m surprised though by how apparently toothless and contradictory this jurisprudence is so ineffectual and actually curbing this custodial violence and at actually replacing custodial violence with truth machines. And throughout the book it seems like Dr Lokaneeta is as shocked and confused by this as I am. I mean I can't help but wonder whether we need to look beyond the courts here, considering police appear to operate with a degree of autonomy and discretion dictated by the monopoly they hold on state power. So if torture and third degree interrogation persist and if truth machines exist and if both manage to exist simultaneously, how does the state manage to continually frame this as a shift in practice and how can we better understand these two tactics coexistence. I’d be curious to know a bit more about how both these modes of interrogation interact with one another and how police discretion plays a role in determining whether to physically interrogate an accused or to send a suspect off to the truth machines.

Similarly the intersection of police and forensic psychologists here raises these fascinating questions about boundaries and police roles. I was struck by a passage in the book in which a forensic psychologist, and Dr Lokaneeta mentioned this, physically torture someone with a pair of pliers and how this represents a sort of joining up of truth machines in third degree interrogation and the delegation of police responsibilities onto non-police actors. How do forensic psychologists, presumably with their own occupational culture, come to be indoctrinated into police culture to this extent and more broadly how does discretion play out for both police and forensic psychologists at this torture slash truth machine nexus. Despite the jurisprudence governing one or the other it seems as though ambiguities with discretion create fuzzy boundaries between torture and truth machines and allow the two to co-exist and sometimes intermingle in violent ways. So before I wrap up, I wanted to talk a little bit about the state forensic architecture that Dr Lokaneeta describes throughout. The architectural metaphor paints a picture of the tangible nature of this enterprise of police violence in India and of all the different components that comprise it.

I’m drawn to the idea of scaffolding something that Dr Lokaneeta invokes later in the book. Scaffolding here is used in the Foucauldian Discipline and Punishment spectacle sense, the raised wooden platform used for public executions. But what with the recurrence of the concept of architecture I’m drawn to this idea of scaffolding not as Foucault would apply it but just as a continuation of the architectural metaphor, scaffolding here being the temporary framework constructed outside a building's facade meant to support construction and maintenance and repair and what have you. Framing it this way helps me wrestle with and advance my understanding of the way Dr Lokaneeta construes of contingency, which is a frequently mentioned concept throughout the book.

I’ll admit I struggled the most with this idea and understanding what the contingent state really meant and its role in police violence and interrogation. But I think this idea of scaffolding in the architectural sense at least helps me comprehend the contingency of it all a little bit better perhaps we can look at police practices here and the techniques police use in interrogation as well as the roles of police and forensic psychologists and court rulings and legislation and all the different components of the state forensic architecture as in a state of constant construction or reconstruction. The quote, edifice to replace torture, as she calls it that is India's forensic interrogation regime has its foundation and its building blocks but each new controversy or case or court ruling involving truth machines rebuilds that edifice structure rendering the state's construction of violence one of broader contingency.

So maybe I’ve beaten this architecture analogy into the ground and I probably don't need to harp on it any further but I do think there might be some more value, and this is the last thing I’m going to do, in unpacking the state forensic architecture by linking it to some STS or STS adjacent frameworks that, at least to me, hold value things that come to mind are assemblages or networks or systems anything that broadly speaking addresses the interconnectedness of actors and technologies and policies and social contexts. Dr Lokaneeta is already kind of operating in this STS territory with her invocation of Haraway and describing forensic psychologists as cyborgs but I think I’ll attack this from the Deleuze and Guattari assemblage perspective, just because I did all this research on assemblage for my comps and I figure I may as well get my money's worth. So from what I’ve come to understand, assemblage involves three features which are the abstract machine, the concrete assemblage and the personae. The abstract machine is this network of specific external relations that hold an assemblage's elements together this network is and the relations are ephemeral but it is still real in that it exclusively and genuinely represents an arrangement of concrete elements. Thus the abstract machine is like a conjunction or a combination or a continuum that binds concrete elements together.

Just as all assemblages have this sort of set of conditioning relations they also have specific elements that these relations arrange. Unlike the conditions that bind these elements together these elements are not abstract but are rather physical working parts of the assemblage. This is what is called the concrete assemblage or the configuration of a machine that grants it its consistency. And finally crucial to this linkage between the concrete and the abstract are personae who are agents who serve as the assemblages operators linking the elements together according to those abstract relations. Now the role of the persona in the assemblage is a bit more complex than what I just kind of sped through here not only do they arrange the correspondence between the assemblages actual physical parts but the personae also arranged the relational conditions under which each machine finds itself.

So assemblage as I’ve kind of blitzed through here may be useful to understanding what is referred to as the forensic state architecture, or to at least understanding this lattice work of relations in which policing and truth machines operate. Here Indian policing is operating as an assemblage, a sort of amalgam of humans and tools stitched together by both the humans’ distinct relations to those tools as well as the broader conditions that either encourage or necessitate that tool's usage like order maintenance or the monopoly of force or the cultural prioritization of confession and truth-finding and the colonial routes in which Indians police- Indian policing is situated. Indian police officers and forensic psychologists are the personae the literal agents and actors, narco-analysis and the truth machines are the concrete elements and they all have their own histories and the relationship between these players and their truth machines are guided by this abstract machine, this network of relations, the legislative background either prescribing or inhibiting their usage, the mechanical affordances or limitations of the machines themselves. So does construing of the architecture the forensic state architecture as a sort of truth assemblage do anything for what Dr Lokaneeta is describing in her book? I’m not sure. I hope so but I do think that discussing the nexus of police tech policing and technology and the state-specific context that bind those relations by using some sort of STS framework might help our understanding of what's going on here by taking a more tech-forward view of these truth machines.

It might also help us further appreciate the complexity of policing and truth machines in India by focusing our attention on its heterogeneous collections, on the heterogeneous collection of human and non-human actors and the very political networks of relations that give these pieces their shape. So I think I’ve kind of rattled on for a bit too long here so I’ll stop it right there, but all to say I had a lot of questions and I greatly enjoyed reading this piece because it gave me a lot to think about, so I’ll pass it back to our moderators, but thank you. Thank you so much, Daniel and Tyler for these very engaged comments. So before I open up the flow maybe I’ll give Professor Lokaneeta a chance, Jinee, to respond there's a lot on the table so if you want to just pick up on a few things and then we can work through them and just in terms of kind of rule setting for the moderation you're most welcome to use the hand function at the bottom of your screen to raise your hand both Bea and I are going to be tracking that and if you prefer you can use the chat box.

We might, if you are on the chat box, we might ask you to unmute yourself so that you can articulate the question, so the idea is to get people to speak as much as possible, thanks. So Jinee if you want to say a few words, comments, respond. Yeah so thank you so much, Daniel and Tyler for taking the time to read the book so closely, I was just you know really both fascinated by your reading, just because of the two you know very different and yet intersecting sort of comments that you had but also from you know just thinking about what are the directions one took and the directions not taken, right, and maybe, you know, I mean I’ll probably just make two comments and then you know we can decide sort of come back to sort of some of what your very thoughtful comments were, so first, you know just trying to think about you know what actually Tyler said, which I think in a sense would be my response to what Daniel's comments are, you know, in some ways, right, that even though the book is called truth machines, right, I think I am thinking about the truth machines primarily as a way to you know rethink the relationship between state violence, right, state power and legal violence, right, so in that sense you know part of the reason why I think, you know, some of the very exciting work within STS, which I’m very attracted to and you know every time I read it I’m very excited by, but I also find that the desire is so much to sort of bring back sort of a discussion of violence, right, or and police violence or state violence to debates on state, right, and in that sense it's it is, you know, I mean in some ways it is both a disciplinary you know attempt to sort of point to how state has been one of the most important categories of study, right, within, let's say political science, but also other disciplines but there is a way in which, you know, the technologies of violence right and the ways it develops over time and the multiplicity of actors who actually constitute policing are never really focused, right, and in that sense you know it was very important for me to, and I would be curious you know if we can sort of talk about that, is there a way in which assemblages or, you know, another framework and you know Bhavani and I have talked about this in terms of infrastructure, right, I mean all those are obviously you can see sort of some kinds of very direct linkages to you know the kind of concepts that I’m thinking about or the kind of phenomena I’m trying to think about, but I think what it ends up not recognizing is something that, you know, I think Tyler sort of brought up, right, that that there is a way in which, you know, state violence and torture is such a sort of like urgent issue right in Indian democracy just as, you know, when we think about police violence in the context of the US has been a urgent issue for such a long time but it was only in the summer last year that it has now become a issue of reckoning, right, for, you know, US as a democracy, right, that you cannot actually ignore it and push it to something that happens in the margins, right, and I am sort of curious to sort of understand, you know, are there particular reasons why, you know, why, you know, torture is it's so prevalent in India, right, and yet it never seems to become that kind of an urgent issue and so far we have very sort of, you know, ideological, right, and sort of explanations for it, right, and, you know, in ways that does not see the kind of shifts that even this experiment with the truth machines does, right, so, you know, to go back to what Tyler was saying, you know, that for the accused it did matter, right, that, you know, whether they get to, you know, basically be subjected to physical torture or these truth machines and I do want us right to look at these, right, what is happening at the at these forensic science labs and what comes in in the form of these truth machines whether you know that made some kind of a shift and I think those shifts may have a way of sort of indicating why then torture does not become, right, such a such a major issue because there is a way in which every time there is a major report of custodial torture the DGP or the director general police will send out circular saying okay just start using truth machines, right, they won't call them truth machines but these are the machines they want to move to and I’m very interested in sort of moving our attention to it while recognizing that, you know, these do not necessarily represent a shift and I think and in to that extent it is trying to sort of use the example of a truth machines to point to multiple sites and then thinking about does it then ask us to rethink the police and the state in a different way. So why don't I stop here and you know there are many, many things that I want to say but I was just curious you know if there are any other comments and then we can come back to. I think folks are still perhaps you know digesting some of the commentary that has just sort of unfolded. Maybe so Daniel and Tyler do you want to maybe pick up on any of those responses, any aspect of the responses for further thing, for further discussion or yeah.

I’m content to open it up to discussion amongst everyone else I feel like I’ve spoken quite a bit and I want to give other people a chance to chat but unless Tyler has anything that he'd like to respond to immediately. No I suppose that's probably best, Daniel you're right, we've taken up enough time, people aren't here to see us speak. Maybe what I can do is open up some of the things that I thought was really interesting in this dialogue and you know as we allow other people to use the hand-raised function or type in comments in the comment box. I think for me what was really interesting is you know when I sort of zoom out, right, zoom back, step back from the book and think more broadly, the book on truth machines puts its finger on a conundrum that you can see play out across a number of domains of life where you know the tech fix is resorted to with ever growing intensity and we would, you know, one can argue that it's also moved from the mechanical to the digital, there are many aspects of defining, you know, it's pretty, its predictability and its kind of spectacular power, right, so is it a rational, so big data is it a rational mean of governance is it, you know, the spectacular power of seeing so many numbers so you can sort of see this play out across many many domains of our contemporary existence and so it is actually really illustrative to see Jinee you take this up in the context of policing and torture and then you show the kind of you know late 20th century, sort of post-war post-1950s emergence of this kind of phenomenon in a place like India, right, so I thought that was a very interesting kind of for me at least it was a very interesting way of thinking about your book and what seems to be kind of driving a number of the chapters and certainly in the comments that we've seen, it's a kind of, you know a question or a challenge that is posed by this tech fix, which is really about, I think ,you can talk about the kind of the technologizing of the law or the law's incapacity or to separate itself or from the technology too, for the legal sphere to become increased increasingly enmeshed in the very tech fix itself and so that was the other kind of theme that you know poses lots of ethical and political questions, which you know I think draw on in your book or draw out in your book I guess what I was really interested in is, you know, how does how do these unifications or sort of how does the law actually appear to the experts who are in the labs and who appear in courtroom testimony, so I’m kind of trying to look at the question in the other way so if you look at it from the legal sphere we think about the tech fix and the way it's kind of taking over legal reasoning but how does how might we theorize or even understand or describe the juridification of this technology. I was just kind of curious to maybe hear you elaborate on that and then the second part of it is also I think motivated by something that a lot of you, both if both Tyler and Daniel have observed and that you brought up, which is that at certain moments the technical expert literally physically manifests as a police officer, right, through the very embodied technologies of torture that the technical fix was supposed to actually sever policing from.

So what we see is a kind of a recursive performativity as well somehow at that moment the tech fix in itself is insufficient to garner the kind of probative but also I would say literally investigative efficacy, right, and so you have to, in a certain way that that the rupture that is being desired by this tech fix doesn't actually manifest and instead what we see is the kind of intensely, you know, the technologizing, as, it's a very awkward term, of the of the league experience. So these were my kind of two responses to the discussion so far. No thank you I mean I think you know and maybe I’ll also link it back to something that I think Tyler brought up but also Daniel, right, that there is a way in which you know we could look at these techniques on their own terms, right, and sort of think about how invalid they are or there is no possibility of scientific validity and so on and so forth and it's true that I in some ways, you know, for me it was very clear that, very quickly, righ,t that basically there was no doubt about the invalidity of these techniques you know and among the scientific communities, right, that in in in some ways it was the way in which you know the state and the police were constructing these techniques that was what was very, very interesting, right, and I think in that sense it is important to distinguish between how the experts present these techniques versus, you know, what are the debates in the scientific community itself.

Can you all hear me I see that Bhavani is, okay yeah, okay. So all right. So the reason why I say that is because I think ultimately I’m I am interested in sort of thinking about what does that then tell us about how the police function, right, and I do want to take that point about, you know, sort of the shift that I, like one kind of shift we talked about was sort of you know from torture to the scientific interrogation regime, right, but the other kind of shift is in terms of how the police are forced to rethink their own framework, right, because of the pressures to say that, okay you know we have to make sure that the people, the persons in custody don't die as a result of this, and I want to take this seriously, right, for me the part even though I’m calling it pastoral in the context of, you know, just mediating, right, this coercion for the person in who's accused, right, it is, it is of life and death, right, I mean for so I do think that in that sense you know the way in which the police themselves construct these techniques as allowing them to give custody over to the forensic science psychologist right to delay sort of, you know, how long a person can stay in custody, right, to actually show that they're adopting science, however flawed it may be, is also an important way of thinking about the Indian police given that Indian police right now if you were to sort of see, you know, basically as I said remand, police remand is often thought of as torture. So I think you know I am interested in seeing some of those shifts.

Now to go back to sort of Bhavani's point is you know the forensic psychologists themselves, right, sort of think about their own role as basically that of, you know, being very distinct from the police right and they would actually say that all the instances that I mentioned of you know how a forensic psychologist uses pliers alongside forensic you know sort of narco analysis that was a, you know, a misuse or a untrained forensic psychologist, right, so for instance psychologists themselves do not think of, you know, that one person as actually, you know, performing the role that she was supposed to play. So I think in that sense I would say that they take their role extremely seriously, as being distinct from the police, as believing in these techniques and basically therefore wanting to expand the state forensic architecture, right and that particular, you know ,and which is why I think that, you know, both,, I think just responding to Daniel's point that the argument about, you know, can you really consider them experts, right, or can you really call them scientific techniques if they're not scientific, right, doesn't work because part of what I realized, particularly with this set of techniques, is that basically there was always a kind of a popular or cultural construction as well, right, I mean think about sort of basically even with the lie detectors in the US what allows for their persistence is actually just myths about it, right, it's as much Wonder Woman as, you know, sort of Pulp Fiction, right, that allows for that and you see in the Indian context, that it's this, you know, showing narco videos, you know, in public, right, just releasing them become a way of creating a kind of a legitimacy, right. At one, you know, on one hand basically because doctors are involved so you know it's a safe thing and second that basically you have, you know, a confession that is coming as a result.

So I do think that, you know, it is it's almost an attempt to really, you know, find those, right, you know, find the places where a unified conception of a police power or state power doesn't actually, you know, you know, represent the experience of these accused with the police, right, and that's sort of what I’m trying to capture through this idea of the contingent state and I think you know Daniel, by actually recognizing that state forensic architecture and scaffold are you know constructed and constantly in

2021-04-03 19:16