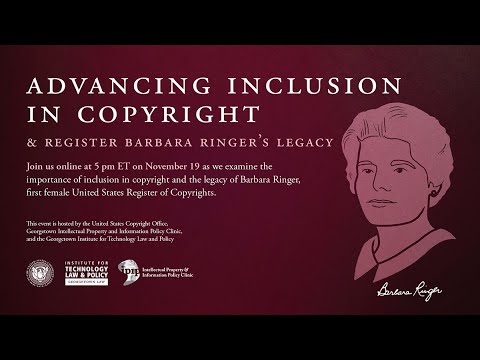

Advancing Inclusion in Copyright & Register Barbara Ringer's Legacy

Thank you for joining us tonight. We're very excited about this. Before we get started, I'd love to just ask you guys to please mute your microphones and to turn off your video cameras so that we can focus on the speakers and what they have to say. And with that, I would love to begin and thank you so much for coming. We're really excited about this. We are excited that you're joining us on November 19th it's on the state for a reason and that is the date on which you register Barbara Ringer became the eighth register of copyrights at the United States Copyright Office back in 1973.

At the office, we are really proud of register Ringer and her accomplishments in copyright and equality. We are pleased to co-sponsor this event with our friends at the Intellectual Property and Information Policy Clinic and the Institute for Technology Law and Policy both at Georgetown Law. I want to thank them for working with us to broaden the discussion on copyright and inclusivity.

Now, I want to welcome a register Shira Perlmutter. Register Perlmutter joined us just last month as our 14th register of copyrights. Though she worked here earlier in her career, she actually was the very first associate register for policy and international affairs with the Copyright Office.

Before she came back to us, she had a storied career in other places, right before she came back she was chief policy officer and director for international affairs at the United States Patent and Trademark Office at PTO where she was a policy advisor to the undersecretary of commerce for intellectual property and oversaw the PTO's domestic and international IP policy activities among many other things. Before she was at the PTO, she was executive vice president for global legal policy at the International Federation of the Phonographic Industry just known as FP to many people. Prior to that, she held the position of vice president and associate general counsel for intellectual property at Time Warner.

We are so excited that register Perlmutter has joined us again at the Copyright Office where she worked with register Ringer. It is really fortunate for us tonight that she is here to say a few words about register Ringer. Register Perlmutter.

-: It helps to unmute, I've learned. Thank you so much, Catie and welcome to everyone. Thank you for joining us tonight to talk about Barbara Ringer and her legacy as a preeminent copyright scholar as well as a champion of equal opportunities. We will be hearing in this program about how equality and inclusion are important aspects of copyright. And I believe we'll be hearing some proposals for achieving a better copyright ecosystem for everyone.

I'd like to start off by saying a few words about Barbara Ringer's life and work. Barbara was an inspiring role model to me personally as well as to a generation of women in copyright. I was very lucky to work with her earlier in my career as Catie mentioned, and she became a friend as well as a regular opera companion. Knowing her was a true privilege. There are very few people who understand copyright and the Copyright Office as well as she did and she drew on that expertise to improve both of them. She was a lead architect of the 1976 copyright act along with her mentor, Abraham Klemstein which of course still endures as a framework today.

She was also passionate about equality in the workplace and advocated strongly on behalf of minorities and women. Barbara's background prepared her well for a career in the Copyright Office and helped form her keen awareness of equality issues. Both of her parents were lawyers which was quite unusual for the time. Barbara's mother was the only woman in her law school class. And despite being what Barbara described as a far better lawyer than me, she never made it to the top. Seeing this impacted Barbara deeply.

And she observed that a lot of her career had been to make up for what was done to her mother. Her mother's experience was not the only thing that shaped Barbara's worldview. Growing up during the great depression and entering the workforce shortly after World War II, exposed her to many instances of discrimination.

While working on her master's degree, she saw that women and minorities in her words were being discriminated against left and right and that there were grave injustices in this country. In law school at Columbia she was one of only six women in a class of hundreds still better numbers than her mother experienced. And she saw that her fellow women in the class were not treated the same as the male students. Barbara's first job after law school was as an examiner at the Copyright Office. She worked her way through many different positions in the office and developed expertise in a wide range of copyright issues both on the domestic side and also internationally. And throughout her tenure here at the office too, she unfortunately saw and experienced discrimination.

She pled the case for hiring more minorities with both the Copyright Office and the Library of Congress. And the issue became personal to her when she was passed over to replace Klemstein as the new register. But Barbara was a fighter. Instead of accepting that decision she brought a lawsuit alleging sex discrimination, as well as retaliation for her advocacy on behalf of minorities. And as of course everyone knows, eventually she prevailed in court and she was appointed the eighth register of copyrights. As part of her work and making the Copyright Office and the library a welcoming place, Barbara encouraged part-time work schedules, women's programs and a childcare center.

So she was ahead of her time in many ways. And on the legal front, her writings demonstrate her view that copyright is integrally intertwined with human rights. In her lecture on the demonology of copyright, she stated, "I believe that a society's duty to go as far as it possibly can go in nurturing the atmosphere in which authors and other creative artists can flourish."

In her eloquent words, if the copyright law is to continue to function on the side of light against darkness, good against evil, truth against newspeak it must broaden its base and its goals. Freedom of speech and freedom of the press are meaningless unless authors are able to create independently from control by anyone, and to find a way to put their works before the public. She saw copyright as empowering, helping individuals assert their rights and exercise their freedoms. I could speak endlessly about Barbara expertise, and I hope that you will read some of the resources on our website that explore her exceptional intellect and career.

I could also talk about her dedication to justice for much longer than we have time for. She was truly remarkable and an inspiration to all of us following in her footsteps. I am thrilled that we were having this event tonight to celebrate her legacy. -: Thank you so much Shira. Well, it's truly nice to hear from people who were familiar with Barbara Ringer at the register . It's register to register.

So thank you so much Professor Perlmutter. I wanted to pass this along to Whitney Levandusky, but before I do just one quick reminder to please turn off your camera and mute your microphones so that we can focus on the great speakers you were about to hear from. So I'm going to turn it over now to Whitney Levandusky who is an attorney advisor here at the Copyright Office in the office of Public Information and Education.

And I am thrilled that she is able to come and talk to you about all of this and moderate to the great panel you're gonna hear. Whitney. -: Hi, good evening. Thank you so much, Catie for introducing me and thank you very much register Perlmutter for the wonderful walk through Barbara's legacy and particularly as it applies to inclusion. Before we begin our moderated conversation portion I'd like to welcome Professor Amanda Levendowski at Georgetown who is the inspiration for Barbara Ringer Day.

Professor Levendowski has been celebrating by Barbara Ringer Day for many years, and she brought this idea of a commemoration and conversation to the Copyright Office. And we are so grateful for her inspiration. So Amanda, would you like to say a few words to kick us off? -: It would be my absolute pleasure. Thank you so much to the Copyright Office and register Perlmutter for her remarks.

I just wanna say a few more words about Barbara Ringer and how each of our speakers tonight connect with her legacy. As Whitney mentioned, I have been in love with Barbara Ringer's legacy for a long time but I actually didn't find out about her until I'd been researching copyright law for six years. And I heard an incredible quote from her 1981 law review article exploring author's rights in the electronic age. And she said, "The 1976 copyright act is a good 1950 copyright law." And as the lead architect of the 76 act, Ringer knew what she was talking about. Her work changed the shape of both copyright law and the Copyright Office itself in so many ways.

But tonight we'll be talking about her dedication to inclusion. And as Whitney alluded to for the past few years I have celebrated the date of Ringer's installation as registered today as Barbara Ringer Day. And I usually commemorate it by tweeting out a thread of her accomplishments but instead I'm excited to do something new this year. And I'm delighted to share a few of those highlights with you today. As the register already told you, Ringer was the first woman to be appointed register of copyright. But even before that, she was a champion of inclusion in both the copyright act itself and at the Copyright Office.

As a lead architect of the 1976 act, Barbara insisted that the new law include dual gender pronouns, he and she for authors, one of the first federal laws to ever do so. But she also fought for inclusion on her way to becoming register as the register mentioned. She became the first woman register because she successfully won a raw lawsuit for sex and race discrimination against the office. In that way, her dedication to inclusion in both copyright law and the Copyright Office left a lasting change on both. One that is reflected in two of our speakers research and writing.

Dean of Florida A&M College of law, Deidre Keller's work continues Barbara's legacy of thinking critically about the role of race and gender and copyright by examining copyright law through a critical race theory lens. Race and gender are also key things of Georgetown law Professor Madhavi Sunders scholarship which explores cultural appropriation and fan communities and also happens to sit at the outer bounds of what Fair use meant in the 1976 act. Because Fair use itself is another of Ringer's lasting impacts on transforming the substance of copyright law. Until the 76 act, Fair use operated as a judicially created doctrine that was guaranteed nowhere but Ringer's drafting of the law changed that by codifying the right to in some cases make use of copyrighted works without infringing the rights. For the first time, these secondary creators were included in copyright law.

And Fair use has transformed copyright law often for the better and in her clinical work, our third speaker director of American universities Glushko-Samuelson Intellectual Property Law Clinic Professor Victoria Phillips has seen firsthand how Fair use can empower clients and she'll share her observations about how pro bono work from clinics can support flourishing creativity. Even as Ringer shepherded the most radical reforms to copyright law in 70 years through Congress, the quote I opened with reveals that she knew the act would be defined by its limitations as well as its innovations. And our hope tonight is that this conversation illuminates those innovations and imagines what might come next for Barbara Ringer's legacy of inclusion in copyright law at the Copyright Office and beyond. -: Thank you so much. So I am so excited, okay.

In truth, we had promised our distinguished panelists that we would come up with a synonym for excited to describe the Copyright Offices feelings for holding this event tonight. And as you can see, I have not come up with synonym. So I am very excited to welcome our esteemed panelists to our screen. And we're gonna be facilitating a conversation tonight and we are gonna have some opportunity for questions and answer after our moderated conversation. And if you could put them into the chat we will be able to gather up the questions and ask them directly to our moderators. So one of the things I want us to think about tonight is that we are gonna be talking a lot about creativity and free expression.

So creative and free expression is part of the fabric of everyday life, right? How individuals make, interpret and share creative works is fundamentally influenced by their identities and lived experience, which in turn, is shaped by local communities and society at large. We at the U.S. Copyright Office have often found inspiration from Justice Sandra Day O'Connor who once called copyright the engine of free expression. In other words, copyright is the infrastructure for how we make, share and interpret expression.

As you've heard so far, throughout her life Barbara Ringer, pushed for a better copyright system, addressing structural issues that limited participation in the system. And of course, we know that the work is ongoing as we're continuously called to examine how our copyright systems work for all Americans and how we can improve visibility of creators and access to their creative works. With us today, are three IP experts whose areas of study spans continents, technologies, and teaching analytical approaches. I'd like to welcome them each and I will be putting a link to their bios in the chat so you can read more about their wealth of expertise and take a look at some of their great articles and speeches and all that fun stuff. So welcome Dean Deidre Keller, Professor Victoria Phillips and Professor Madhavi Sunder.

Thank you so much for providing your insights today. Let's start with a foundational orienting question. We are going to be talking about access and inclusion and let's just spend a quick moment to make sure everyone can grasp what we're going to be referring to. So what do access and inclusion mean? And perhaps Dean Keller, would you like to get us started? -: Certainly.

So access and inclusion in the copyright context specifically sort of gets back to what register Perlmutter made reference to in Barbara Ringer's demonology of copyright. Broadening the base and I think recognizing that there are values at stake in addition to economics. Nothing that I'm saying there is revolutionary. In fact, there are values at stake in addition to economics, I'm pretty much quoting Professor Sunder. I won't steal her thunder but if you want a book length treatment of that conception Professor Sunders "From Goods to a Good Life" is a good a place to start as any. And so when we speak about access and inclusion in the context of copyright, we're certainly speaking about whose perspective is taken into account and what values are we endeavoring to uphold and and put forward.

And Ringer also makes reference to artists, authors flourishing and while I think that is very important I think we also must ask, who else in our society copyright can support the flourishing of, so what responsibilities does copyright have to ensure the flourishing of students? What responsibilities does copyright have to ensure the flourishing of citizens? Those are all relevant questions as we consider access and inclusion in this context. -: Thank you. So Professor Sunder, since Dean Keller give you a shout out, would you like to add? -: First, if you allow me to, I just wanna say thank you for inviting me to participate in this super exciting, let's just own it, Whitney. And I wanna say first, thank you to register Perlmutter for having this event and to you Whitney for really bringing the issue of inclusion front and center. I mean, I've been writing in this space for just over 20 years but to have an official Copyright Office embrace of these values that we've been arguing have always been a central to copyright, and affirming that I think means so much. So thank you.

I also have to give a shout out. I'm gonna give shout outs to Professor Keller for sure, Dean Keller, actually, for sure during this time. And I'm so excited to have this discussion with our co-panelists here but I have to give my first shout out though to my dear colleague, Professor Amanda Levendowski. Amanda I think has really grasped to the core this project of representation and justice. And here in this context by first naming Barbara Ringer Day, just proclaiming it, putting it into history.

So naming and then tweeting, that's the 21st century way. You name, tweet and then Amanda, at some point you'll have to tell us is there a trademark involved as well? It's just wonderful to see this invention of tradition, the writing of history and we've got the authors of all of that right here. So I'm excited to be here. Okay, so the big question what do we mean by access and inclusion? I loved the way Dean Keller opened that up. Really just broadening our lens to I think, the first, I would say more narrow way of thinking about it is just who has access to being able to register a copyright, right? Who has access to the Copyright Office? Do people have knowledge about the Copyright Office? Do they have the skills? Do they have access to legal representation? So I think we could think about it in that way, which is, I call it narrow, but I don't mean to diminish it because that's still super important and I will love to talk more about educating people about their legal rights and legal processes in this conversation.

But I think how Dean Keller opened it up beyond that to talk about, who does copyright affect. It's not just the authors who are recognized but the consumers who learn from, engage, and flourish and grow by accessing the works. And she talked about students and access to educational materials. So I do think absolutely when we think about inclusion we need to think about not just the producers of knowledge but the consumers of knowledge and all of us how we work together in a knowledge society. So I loved that framing. I guess I will just end by telling you how I kind of tend to frame these questions of access and inclusion.

And I think about it really with respect to two big picture questions. One, aside from the procedural, who gets their foot in the door in the Copyright Office? It's just more conceptually, who is even recognized as an author? So we have still so many structural and cultural biases with respect to who we see as creators as knowledge producers and who we see as mere consumers or the objects but not the subjects, the owners of knowledge. So one, this is partly the representation question in terms of who gets to tell the story? Who creates our culture? And that's who we recognize as an author but it's a really important technical term that doesn't get applied to everyone equally.

So one, that's the representation question. Who is an author and what are our impediments still to having equal access to that coveted title? The second question is really the remuneration question. It's the distributive justice question and that is, who makes the money and is any of it mine? And copyright as a system of property and as an engine of creating wealth in a knowledge economy and how do we see this as a system of distributing wealth or being itself a cause of mal-distribution of knowledge and power.

So I wanna end there with just those kinds of big two, big picture question. Who is an author and who makes the money from authorship. -: Great, thank you so much, Professor Sunder. I really appreciate the point that you made about expanding or broadening the definition of who an author is. 'Cause I think some so often the way that we frame copyright is there that there are people that are affected by copyright and that there are people that are not affected by copyright. And sometimes that comes down to our definition of an author or the formality of an author where, but on the other hand, when we think about copyright law, the definition of authorship is fundamentally broader so that there seems to be like a gap between the popular understanding of authorship and sort of its possibilities under copyright law.

And so I wonder if a Professor Phillips. So we've heard a couple of things about broadening the base. How do we first identify what we think of the basis and what are some strategies that we might use to help broaden the space? -: Well, thanks Whitney. And I wanna thank you again, just like Professor Sunder said, I wanna first congratulate register Perlmutter, fantastic that she's got really big shoes to fill, really big shoes. I think we all could agree on that. And also thanks to my colleague as well in the clinical community Professor Levendowski for being a Ringer fan and sharing her story with all of us.

Wow, it's so important and I tell my students it's so important to know the people and the stories of the people who shape our laws and policies. And I've been plugging the Ringer fellowship for nearly my whole career. And I didn't know about Barbara Ringer.

So thank you Amanda for that. And I think in terms of my lens on all this, it's just such a privilege to be still practicing law in the Academy. And I think of our new community of IP technology, arts and entertainment law clinics as real laboratories to see the things that the students and we all know to be in the doctrine and in the policy impinge on people's rights.

Impinge on authorship, impinge on creativity. I started the clinic in 2,000 so it's been nearly 20 years. And so things have really changed in terms of the conversations that we're having. The internet was new. The browser had just been invented a handful of years before. And I think that evolution has really shaped who's a producer, who's an author.

I have a colleague in town who coined the term pro-sumer we're not just consumers of musical anymore. We are of media and cultural works. We are producers as well. When I see clients with rights, we try to protect them. We're not a Fair use clinic per se. But when we see clients who are trying to do really creative things and add to culture and participate in culture, we try to help them within the limitations and exceptions that the law provides and create opportunities to increase cultural production, not impinge it because a lot of the people that we see in our clinic are the people we're talking about.

We have a lot of female clients. We have a lot of people who have not had access to the system before, because there hasn't been a lot of pro bono work in this area. And that's really the privilege of working in the IP clinic spaces is we provide pro bono service to people in the education. I think it's access to justice. You need the access that my colleagues talked about and you need the justice, the law should reflect all of us.

And it's a two piece approach like that. -: Thank you. So there's an interesting word popped up in each of your opening answers and that story. So each of you spoke to the importance of stories and who is telling the stories and when they get the opportunity. So how can we learn from people and their stories when they feel left out or otherwise unaccounted for, and why is hearing from more voices important to equal access to copyright and democracy at large? I just threw that out there. Professor Sunder, I see you've unmuted.

-: Jump in and we can bounce around a little if you want, but I think, I'm currently working on a big project around cultural appropriation. And so your question makes me think that I don't necessarily think the problem is that diverse peoples cultures and stories aren't being represented but often they're being represented by powerful majority owned corporations and so that's why I emphasize that just as important as who is an author is who's making the money from the stories and the culture. So if we think of diverse forms of art in the form of fashion, for example, we just see case after case of traditional native designs, South American designs, African designs that are copied wholesale by Western corporations, Western high-end fashion designers where they're benefiting tremendously financially without giving any recognition at all to the original creators of these works, communities. In many instances, their local communities but often there are also individual artists living, breathing people today, who are innovating around traditional methods and traditional designs but they're creating new works but being overlooked. So they're often being overlooked and they lack the power to either fight the corporations or to obtain a good deal for themselves in that cultural exchange. So I think it's not just a question of getting diverse stories out there but who is telling the matters.

It matters first from the perspective of just recognizing the dignity of individual creators from around the world when we misrecognize them and say this is just traditional knowledge, it's ancient and it's graded by groups, millennia pass but not created by individuals is today. I mean, the power of say her name, that this event, Barbara Ringer Day but obviously black lives matter, say her name. Well, it's the same with these creators.

There are living, breathing, innovative, cutting edge artists today in diverse communities around the world. So we need to recognize their names and recognize their work as their own. That's not happening. So that's kind of one question about stories and getting them out there. And then the second side of it is, the recognition side is the first part but the second side is they should be educated about their ownership of rights in their works, their fashion, their art, their music, their stories and empowered to protect them. And again, a fair and just copyright system involves not hoarding, but fair and equitable exchange of culture.

So I think to my mind the story issue is very complicated. It's not just stories that aren't getting told but who's telling them and who's benefiting financially from them. That matters. -: I wanna amplify and kind of underscore something that was implicit in what Professor Sunder just said which is this conception of power. The mere fact that we're sort of talking about power and how it operates in copyright is remarkably refreshing.

So I have not been doing this work as long as Professor Sunder has or Professor Phillips. But what I can tell you is when I started down this road 10 years ago and articulated my sort of scholarly agenda, I was warned away from anything that wasn't sort of, that didn't fit cleanly in the law and economics framework. And this is not a conversation that can take place within that framework. And it really is the recognition of power as operating in this space really is the contribution of critical legal scholars and critical race theorists. John Tehranian has a paper that was published in 2012 called, Towards a Critical IP Theory.

And in it, he defines critical IP theory as the deconstruction of trademark copyright and patent laws and norms in light of existing power relationships to better understand the role of intellectual property in maintaining and perpetuating social hierarchy and subordination. And so I think that theoretical frame helps us to see those places where what Professors Sunder said is really clear. It's not just about whether the story is getting out, it's also about who we recognize as the author of that story. It's also about sort of the dignitary aspects of that.

And it's about understanding how the power relationships influence the narratives and influence the stories. -: Yeah, and I'll just piggyback on that. I mean, the fact that we're having this conversation and the fact that we're celebrating Ringer as Professor Sunder says, naming her, saying her name in 2,000 when an outgrowth of the IP clinic that we started was to create a series of intersections IP and antitrust, IP in the first amendment. And one of the ones that we wanted to do as a school that was founded by women who couldn't get into law school because women were not at the turn of the century, mentally capable of being lawyers.

So the Washington College of Law was founded as a co-ed law school, but that would include women. And we wanted to do this intersection of IP and gender. And we looked around for scholarship and there was so little. Professor Sunder had started writing and Rosemary Coombe, and we calmed it and we invited friends and tried to get people at this conference to present.

And just what Dean Keller said, it was risky scholarship at the time. People really didn't wanna do that as their major academic work. And we went from the unmapped connections to then we had several volumes of our journal of gender and policy. And then we started calling it, mapping the connections because there actually started to be scholarship there. And Kevin Greene had done some stuff on race and IP, but these conversations, it's so wonderful to see the awareness.

'Cause I think awareness and education is the first step. Are we gonna change the copyright act? We're still waiting for the next great copyright act. I used to practice communications live and waiting for the next communications act since 1934.

Changing laws is really hard but educating people and promoting awareness and changing the culture and the way people operate and creating new norms around copyright and around cultural appropriation and what's right, and what's not right. And by giving these people a voice whose things have been, whose property has been taken, whose cultural artifacts have been taken and whether it's IP clinics or pro bono representation, VLAs around the country. When we give these people who have been so hurt by the system, and so unempowered and they've been out of the market so often. And so many of the gender things from quilting to fan-fiction have been purposefully out of the market. Really, it's more of a sharing economy and Professor Sunder has written so brilliantly about this but I think when there's awareness and there's help, you can start to see change.

And it starts in academic articles and then it filters down to clinics. And I feel like we are in a sea change of activity to make this more just system. -: So we've talked about the awareness, so that Professor Phillips has identified, it's a combination of awareness and help. So when we talk about access and inclusion so Professor Sunder has identified that it's not just the stories, but it's also about the operation of distributing those stories and how we recognize value whether economic or non-economic value in distributing the stories.

So what can we do, which I realize is like a question that just like, super broad and expansive and could be engaged with through many to publications and journals. But the thought is that we have to be proactive and to encourage people when it comes to using the system. And education is one component of it, education about the system, about rights and appreciation for rights and for ownership and claiming one's own creative expression.

What else can we do to make, can everybody give us an example of something that we can do to be more inclusive, to help to shift the power or expand the power and who has it? -: I think, just one suggestion. One thing that I'm starting to see is I think data would be really helpful. I don't know, we do copyright applications all the time in my clinic and you all certainly know the forms better than I do, but you say your domicile and you say your date of birth which of course one needs for duration and for copyright like things but we don't have data of who owned, who has copyright ownership. It's like the patent office and wonderful scholars have done the work and tried to figure out because that data is not kept. And I think, if we sort of saw that because I read a statistic today that 45% of small businesses for example, are owned by women which is crazy to think about, but almost 95% of them are sole proprietorships and very small. And this is the clientele that I deal with on a daily basis.

And I feel like more data just, and I'm not such a data person, everyone around me seems to be a data person but I think that would be an interesting thing to undertake some studies about what the ownership ecosystem looks like in the Copyright Office, in the trademark office, in the patent office as an IP generally would be one thing that would be an interesting tangible thing we could try to do. -: The thing that I will add to that is really a recognition of the way that having economic wherewithal affects participation in the copyright system. So Fair use is kind of, I'm gonna pick on Fair use a little bit. Fair use is kind of the perfect example of this. Fair use is an affirmative defense.

So if I am a producer of content, and I post, I have a son, who's a musician he posts a video and it gets taken down because of the digital millennium copyright act. That's not a fight that he can fight, generally speaking. He's 18, he has nothing. So that's not a fight he can fight. And, just recognizing that that's a barrier to entry and then thinking about how we can solve that problem I think is hugely important.

Professor Phillips is making reference to pro bono services in this area and how scant that is when I was practicing law a long enough time ago now, there was very little in the way of folks who were engaged in big law, doing IP law providing pro bono services. That's something we can do pretty immediately. And just recognizing, if we don't see that problem we can't fix it. And so when you think about what it costs to defend an infringement suit, I have had occasion to march down that data, it's expensive. Most people, and even many entities simply cannot do it.

Cannot undertake that kind of defense. And so once we see that problem, we can begin to address it, but until we do, we can't. -: Great question.

I see lots of really good suggestions for things that we can, practical things that we can do thinking about access the fees to copyright, more clinics and public interest, small claims, copyright court has mentioned here but the work of Professor Phillips and your clinic and Professor Levendowski's clinic here at Georgetown, I think all of that's really important. More education around rights and working with various community lawyering groups. I've heard from a number of folks that work to empower local communities that there were so many young artists that really want to learn more about their legal rights with respect to protecting their work. So I think all of that needs to be done and I support all of it. But Whitney, I have to say that the space that I'm in right now, is that we are not really just, we shouldn't just be focusing on these kinds of practical fixes.

That the moment that we are in as a society, thinking broadly reckoning with structural racism and that that conversation has got to be where we really more deeply engaged with this question. And so I've been really thinking about the whole history of property law like rights and land in this country. We all more readily recognized as being about the creation of wealth off other people's backs.

It's about dispossession of native American land and dispossession of African slave labor. And in fact, there's a big dispossession story in intellectual property too. And in terms of the corporations that are making grand amounts of wealth with respect to video games and music and fashion today off of the creativity and the creative works.

So partly it's, this is happening today, and we need to recognize it, but also that we still are reckoning with the vast inequality that was created by the failure to recognize black slave, not just physical labor, but intellectual labor and the loss of generations of wealth because of those failures. So I think there's a really, that we're at a moment societaly for a deeper reckoning with respect to why we are here, where we are today and that means going back centuries, frankly. And I think that that includes thinking about those issues in the intellectual property space. How did we get here historically? And how are we still reproducing these inequalities today? -: Could I jump back in here really quickly? So I think Professor Sunder is absolutely right. And interestingly, it brings us back to register Ringer's demonology of copyright in which she talks about how the 1790 act came about in this, she calls it like a nationalist fervor. And when we think about who that means the copyright act was made for, it very obviously excludes black people.

It very obviously excludes women. It very obviously excludes lots of folks. And so we definitely are still seeing that today. And I'll give one more resource shout out because when I read that I was like Barbara Ringer was really ahead of her time but a very recent book by Anjali Vats who I'll give the disclaimer is a very good friend and my co-author on various things but she has a book out called "The Color of Creatorship" that just came out this year in 2,000, Stanford university press. And it pulls on this thread of the history of exclusion in intellectual property in America and really does a deep dive on that question and what we mean when we think about creators in American culture and how that meaning is reflected in our laws and our legal decisions, et cetera. -: So is the work, I guess, retrospective as well as future looking.

So there seems that in order to envision what might come next or what might be the best way to promote free expression, we have to also look backwards. And so it sounds like some of the practical steps that we have to take is to first sit with ourselves. And sit back and do the analytical work before moving forward. So it's like sitting and thinking about it and engaging with the uncomfortable truth that we find before then finding future solutions. Does that sound.

-: Absolutely. Yeah, if you don't reckon with these power differentials and this history, then can't get from here to a just copyright law. -: And we're such in a moment to sort of agree with both of my co-panelists. We were such a moment where everyone is focused on this. We need to seize it in our little corner of IP.

It's so important, I've worked for years with Suzan Harjo on the Washington football case. Had my students work with her. She's one of my idols and friends and heroes. And I wrote many briefs on latches and horrible legal doctrines but what moved the needle was this moment we're in and the pressure because of the education and because of saying her name, saying their names. This is why this moment cannot be lost.

I so agree. -: Another part of this reckoning is thinking about our own implicit biases, and that includes the biases of the USPTO when it comes to trademarks it includes the biases at the office of copyright registration as well. And how do we see different applicants. Do we see them differently? So part of it is asking questions about structures of how we define an author and how we look at Fair you. So, part of it is thinking about the doctrines and, how did they evolve? What are their disparate impacts? But also it's just the applicants themselves and the works themselves. And we are not free of our cultural notions about what is art, and what's not art and who's an artist and who's not an artist.

So I think part of it could be implicit bias training in for all of us again and again, but recognizing that we're as much as we wanna change the system, we're part of a longstanding system. And we need to think hard and critically about how we've been affected by it and how we can change. -: Yeah, and I'll piggyback on that, just to say that one like really crystal clear version of this and someone posted about it in the chat earlier is about the notion that an author is this individual person sitting in their basement, creating things when so much of creativity is communal. But when we think about what our copyright system is meant to protect it is that individual creation. It is that enlightenment notion. Again, I'm not being creative here at all.

I'm relying on the work of Martha Woodmansee and Peter Jaszi, who speak to this most beautifully. And on the work of K.J. Greene who really talks about in lady sings the blues talks about this problem. That we perceive of what constitutes art as this thing that's made in isolation. But so much of what constitutes art and so much of what is frankly American culture is not created that way, it's created in communities and very often in communities of color. -: Thank you.

Before we go to a couple of questions, there was just a comment from Professor Greene in the chat that sort of links up a lot of the points that we've made. Professor Phillips, her hunger for data and where do we find it? And then the sort of identifications of like there are limitations in terms of accessing Copyright Office services. There are limitations in terms of identifying who the author is. The scholarship of Professor Greene talks about the limitations of what made it into the Copyright Office record.

And Professor Brandeis over at GW had published a paper on representation and registrations, and there were gaps that he identified and even then, interpreting the data required some inferences so the data that we're looking at and the public record that we're looking at has a wealth of good information, but it also has absences. So I just wanted to give a quick shout out to Professor Greene's question which is how can we have any confidence in the records of the Copyright Office and why can't the Copyright Office verify authorship claims and registrations. And so part of it's, I think any confidence in the cut records of the Copyright Office, there are strengths and weaknesses to any sort of public record. And I guess in terms of helping to build a stronger public record and more representative public record, is it a question of just access to government services and educating people about their authorship contributions or is there something else that we can also be thinking about? -: That's tough, Whitney. I mean, that's tough. I know that USPTO has gone to great lengths to try to create different fee structures for micro entities and create more offices of independent adventures, more outreach because I think so many patent applicants had gotten swindled by these invention submission corporations.

There was a rationale for doing that. And it's funny 'cause in my clinical work with our clients have limited means, the copyright is like a good option at the fees that the office has. It's the trademark in the patents that are usually out of the question. So copyright is pretty accessible if you have the free legal services and the free advice to know what's worth filing for and what you should protect 'cause I think working within the system we have is for now, what people need to do. -: Thanks, and I think that your point about the Copyright Office being accessible relative to other IP systems is true.

If I might, just be a little Copyright Office superior for a second, but there's always the emphasis and something that we put up at the top is that there's always work to be done. So while the Copyright Office, we are always there for everybody, the process is continuing. And I think that that's one of the goals that we had for this conversation tonight is to sort of help that process, help us all think about how we can be more open and accessible in our copyright system. And so I think we are out of question time, unfortunately, it was just too good guys.

So I think before we go to our breakout sessions where we'll be able to chew more on the issues that we talked about in here, I think Catie has just a few final words, a few final thoughts for us before we move on to our networking. -: Thank you so much, Whitney. And thanks to everybody in the panel.

This is fascinating and as someone who was almost a women's studies minor back in undergrad, it's really exciting to be able to review it especially kind of marrying the two loves of my fear of life at least is kind of equality issues and copyright. I just wanted to say, as far as the discussion goes we're really excited to break into the breakout rooms and dive in there a little bit more deeply. We hope that whoever is around will continue to join us and work with us there.

I will say echoing Whitney that we at the Copyright Office really, really encourage anyone to register. Everybody, we want to get everybody. And we want to make sure that everyone's voice is heard. This program is just one part of our commitment to equality which we really believe in very deeply. And our examination process as, I can assert is not really, does not have, suffer from those issues in the modern era.

And I would like to just vouch for the really great work that the Copyright Office does. Not me, I'm not the examiner, but the registration staff and they really do care.

2021-02-08 02:38